The orders threatened to withhold federal funding from states that do not comply.

President Donald Trump wants to end the cashless bail system across the United States as part of his push to lower crime.

To that end, he signed two executive orders on Aug. 25, one targeting the District of Columbia and the other addressing the states.

Here are a few things to know about those orders and the system Trump seeks to overturn.

What Is Cashless Bail?

When a suspect is arrested, a judge often releases him or her to await trial and may require bail—a sum of money—to be held as a bond to ensure that the suspect shows up for trial.

Cashless bail, sometimes called “bail reform,” allows suspects to be released without posting bail for some crimes, usually misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies.

Illinois is the only state in America that has completely eliminated cash bail, while other states, including New York, California, and New Mexico—as well as the District of Columbia—have restricted its use.

The states’ laws are not all the same.

Laws in the District of Columbia generally direct suspects to be released without bail, although there are exceptions for murder and armed assault with intent to kill.

New York’s bail reform system used to have such requirements, but in 2023, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul removed a provision that stated that judges must use the “least restrictive means” to ensure defendants show up for their trial.

What Do Trump’s Orders Do?

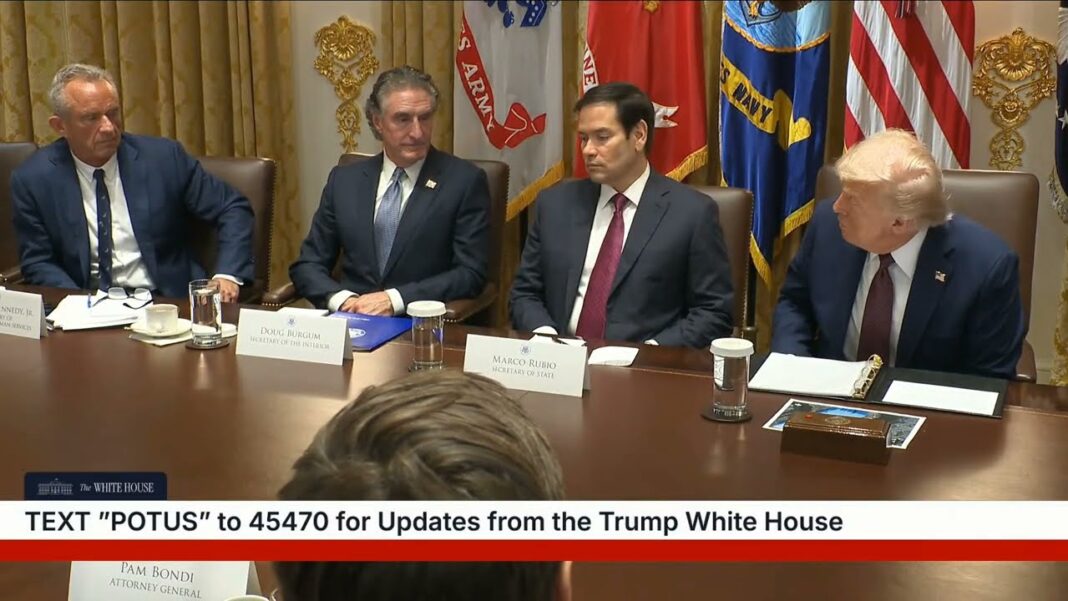

One of Trump’s executive orders gives Attorney General Pam Bondi 30 days to compile a list of state and local jurisdictions that use cashless bail policies for suspects who are alleged to have committed “offenses involving violent, sexual, or indecent acts, or burglary, looting, or vandalism.”

The jurisdictions that continue to use cashless bail will be stripped of federal funding, the order states.

Trump’s executive order targeting the District of Columbia asks Bondi to “press the District of Columbia to change its policies with respect to cashless bail” and suggests that the administration may withhold funding or federal services if the policies remain in place.

The District of Columbia order also states that, whenever possible, suspects should face federal charges and be “held in federal custody to the fullest extent permissible under applicable law.”

This provision ensures that “criminal defendants who pose a threat to public safety are not released from custody prior to trial,” the order states.

The threat of federal charges also means that defendants, if convicted, may face harsher penalties for the same crime than if they were charged under local law.

Federal offenses, especially those that are drug-related, often carry a minimum prison sentence.