Collective pledges and reverting to landlines have spread through homes, as parents try to protect children from social media.

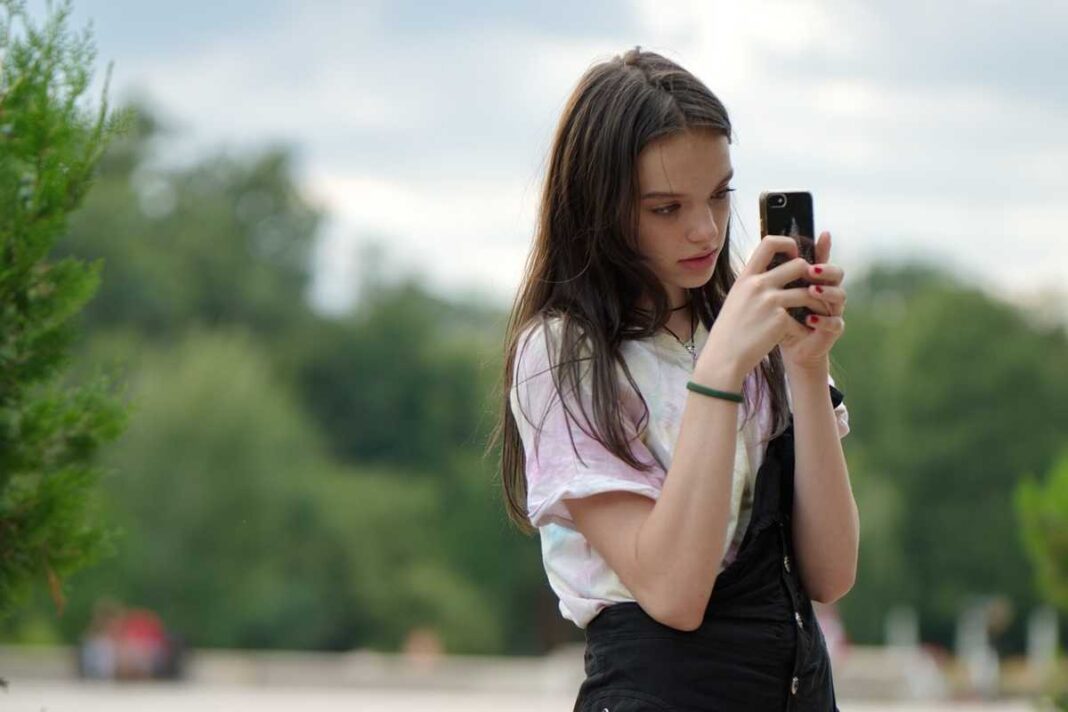

Parents across the United Kingdom are increasingly taking matters into their own hands when it comes to smartphones, including making collective pledges, promising not to buy phones for their children until a set age.

Today’s mothers and fathers say they feel like the first generation forced to confront this challenge.

While younger children can be persuaded to wait, many parents say the real pressure begins around ages 10–11, when peer influence at school makes resistance far harder.

According to regulator Ofcom, nine in 10 children own a mobile phone by the time they reach 11.

Parents are joining no-smartphone pledges designed to remove the argument that “everyone else has one,” and to ease the peer pressure children face.

The UK’s Online Safety Act, passed into law in 2023 and coming into full effect in 2025, mandates that online platforms and apps protect children from harmful content by using age-assurance tech to block access to pornography, illegal material, and content that encourages self-harm.

300,000 Parents

Will Orr-Ewing, a father and founder of Keystone Tutors, is seeking a judicial review of government guidance as part of a campaign to get smartphones banned in schools.

Orr-Ewing told The Epoch Times that he supports grassroots campaigns, such as Smartphone-Free Childhood, which began with two mothers and school friends Clare Fernyhough and Daisy Greenwell earlier this year.

Smartphone-Free Childhood is a fast-growing parent network built around WhatsApp subgroups in which parents share articles and research, and a collective voluntary pledge to wait until their kids are at least 14 before they’re given a smartphone.

Greenwell told The Guardian last year that an alternative solution could be a “brick phone,” that allows text and calls only.

“The peer pressure instantly dissolves if your child knows there are 10 children in their class who are getting a brick phone as well—and not a smartphone,” she said.

Orr-Ewing said, like them, he was driven by a parental “protective instinct” that smartphones are pretty dangerous to children.

“They set up a WhatsApp group themselves. They posted about it, saying, ‘If anyone wants to kind of come at this issue, take some collective action, please join our subgroup.’ They had 1,000 people join in the first 24 hours, 2,000 in 48 hours, and they’re now up to over 300,000,” Orr-Ewing said.

“I think that speaks to a kind of … parental instinct to protect their children in that group. People have lots of different motivations and thoughts, but … I think there’s a sort of central, kind of uniting factor of what it’s like to be a parent today,” he said.

Orr-Ewing has also been working with schools to highlight the risks posed by smartphones on premises.

He said that while parents can protect their children at home, schools pose a distinct threat: despite every school having a duty of care, it’s hard for them to police smartphones on sports fields or in the toilets.

This means, “basically, wherever there’s not a teacher sort of looking directly at them, they’re accessing their smartphone,” he said.

Parents have reported children being shown graphic videos, from violent fights to pornography, on their very first day of secondary school. Yet only about 10 percent of schools have a strict no-phone policy, he said.

By Owen Evans