‘There are lots of other authorities that can be used,’ Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said.

The Trump administration is confident that the Supreme Court will uphold President Donald Trump’s global tariffs. However, if the White House does not prevail, there are other options, according to U.S. officials.

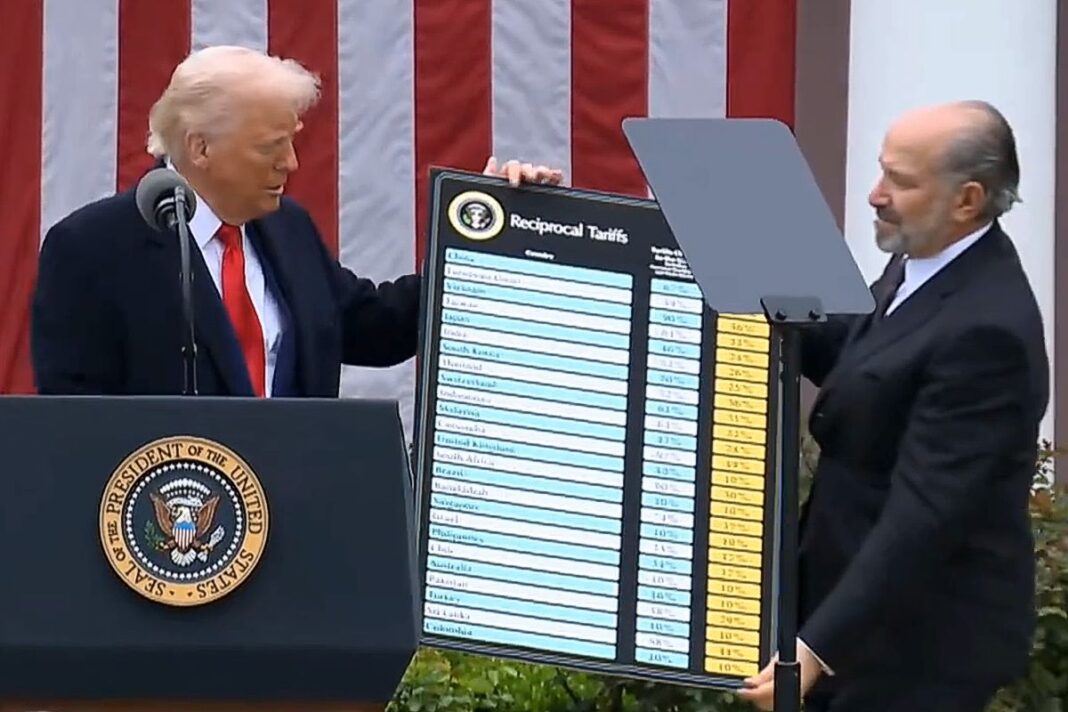

The high court heard arguments on Nov. 5 on whether the president overstepped his authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) by imposing sweeping tariffs on U.S. trading partners.

Commenting on the Supreme Court hearing, Trump told reporters on Nov. 6, “We did very well yesterday,” noting that a negative tariff outcome would be “devastating.”

“It would be a shame,” the president said. “It would be somewhat catastrophic for our country. But I also think that we’ll have to develop a game two plan, and we’ll see what happens.”

During the hearing, multiple members of the court expressed skepticism about the defense of the president’s wide-ranging tariffs, which could indicate that they may be reversed.

Although the 1977 law is the preferred option to enact the president’s trade agenda, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said other tools are also available.

“There are lots of other authorities that can be used, but IEEPA is by far the cleanest, and it gives the United States and the president the most negotiating authority,” he said in a Nov. 4 interview with CNBC’s “Squawk Box.”

“The others are more cumbersome, but they can be effective.”

The Tariff Act of 1930

Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930, commonly known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, empowers the president to impose new or additional tariffs of up to 50 percent on imports entering the United States.

This authority may be exercised when a foreign nation is found to have levied excessive tariffs or erected significant non-tariff barriers against U.S. goods.

What might make this an attractive option is that no official investigation is required and that there is no limit on the duration of the import duties.

Trade Expansion Act of 1962

President John F. Kennedy signed the Trade Expansion Act into law in October 1962, establishing Section 232.

This provision allows the president to impose tariffs on imports that pose a national security threat.

Trump used it to justify import duties in both his first and second terms on steel, aluminum, and foreign automobiles. According to analysts, expanding its use to other sectors would require stretching the law’s original scope.

Trade Act of 1974

Introduced by Rep. Al Ullman (D-Ore.) and signed into law by President Gerald Ford in 1975, the Trade Act of 1974 expanded presidential power over trade negotiations and enforcement.

The law established fast-track procedures, enabling the executive branch to negotiate trade agreements with greater speed and leverage, subject to streamlined congressional approval.

Officials and economic observers have concentrated on the law’s two provisions: Section 122 and Section 301.

Under Section 122, the president can implement tariffs of up to 15 percent for 150 days on imports from countries running large trade surpluses.

The law also allows for limits on the volume of goods arriving from overseas markets and does not mandate a formal probe.

To date, Section 122 has rarely, if ever, been used by presidents.

Section 301, meanwhile, grants the president sweeping authority to address unfair trade practices through a broad array of measures, including tariffs, sanctions, and other retaliatory actions.

that the administration believes violate trade agreements or discriminate against U.S. commerce.

However, before penalties can be imposed, the administration must clear two procedural hurdles.

First, the trade representative is obligated to seek a negotiated resolution with the offending country.

Second, the United States must attempt to resolve the dispute through the World Trade Organization before resorting to unilateral action.

By Andrew Moran