Beyond the noise, the core of the new guidelines is to go back to real food and common-sense healthy eating, an expert says.

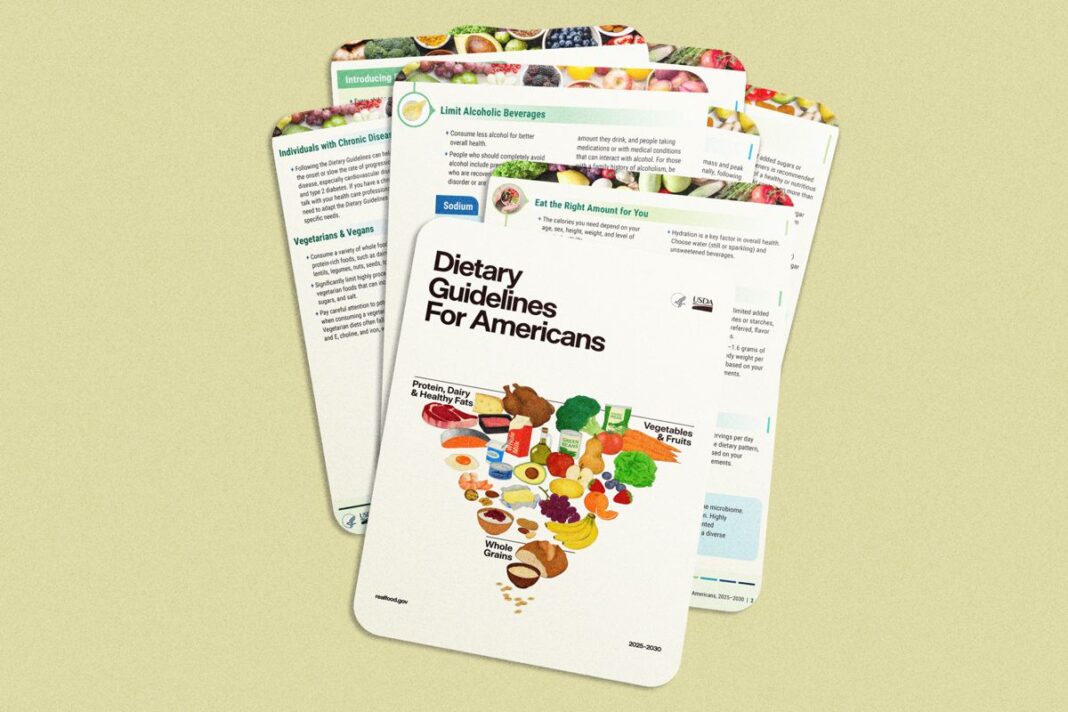

The new Dietary Guidelines for Americans mark the most significant change to the guidance since 1980. They encourage people to eat more animal proteins and fats, and avoid highly processed foods, while putting a clear focus on eating real, whole foods.

Here, we’ll break down all the major updates to the guidelines, the scientific reasoning behind each recommendation, and the debates and certain concerns raised by experts in different arenas.

1. Eat Real Foods, Avoid Highly Processed Foods

The new focus on eating whole foods over highly processed foods is common sense, said Lidan Du-Skabrin, who holds a doctorate in nutrition from Cornell University.

While we know that many nutrients from whole foods, such as antioxidants and vitamins, are beneficial and essential, there are also potentially many more nutrients still unknown to us, Du-Skabrin said. Eating whole foods helps ensure people do not miss out on essential nutrients.

The new advice, from Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030, differs from earlier guidelines, which did not clearly tell people to reduce ultra-processed food intake.

Because there is no consistent definition of ultra-processed foods, and despite more than 200 published studies on ultra-processed foods listed in PubMed, most studies are observational and show associations rather than prove cause and effect, Richard Mattes, a nutrition scientist and former member of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, told The Epoch Times in a previous interview.

The new guidelines came with a scientific foundation report and appendix. Authors of the report defined highly processed foods as any food or drink primarily made from food extracts—such as refined sugars, grains and starches, and oils—or containing industrially manufactured chemical additives.

Using this definition, highly processed foods and drinks account for about 60 percent of the calories eaten by Americans.

In the scientific foundation report, researchers reviewed 27 meta-analyses and found that eating more highly processed foods is linked to increased risks of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cancer. They also identified a dose-dependent relationship, meaning that the more highly processed foods people ate, the greater their health risks.

2. Eat More Protein, Especially From Animals

The new guidelines suggest a 60 percent to 120 percent increase in recommended protein intake and place particular emphasis on animal proteins over plant proteins.

In the report accompanying the guidelines, the authors noted that previous protein intake recommendations—including both the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) and the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)—are minimum thresholds intended to maintain nutrient adequacy. The current RDA is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

The authors sought to determine whether eating more than the minimum protein recommendations had additional health benefits.

Their review of 30 clinical trials examining higher protein intake found that eating 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight was associated with improved weight management across most age groups.

Christopher Gardner, a professor of medicine at Stanford University and a member of the Scientific Advisory Committee for the new dietary guidelines, said he was surprised by the higher protein recommendations. The Scientific Advisory Committee met for two years to develop and write its dietary recommendations, which were submitted to the U.S. government in December 2024.

“Our statement, which was 400 pages long and had a 1,000-page supplement and was very rigorous, suggested that protein was not an issue of concern. In fact, we said fiber was more of an issue of concern, and that to hit both protein and fiber, it would be best to have more beans, peas, and lentils—or technically, legumes—and less red meat,” Gardner told The Epoch Times.

The U.S. government has not been able to set an upper limit on protein, which speaks to its relatively safe profile.

In 2022, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) conducted a review to see if there were adverse effects from eating a high-protein diet, defined as about 3.0 to 4.4 grams per kilogram of body weight, and found few adverse effects. As a result, the agency concluded there was insufficient evidence to establish an upper limit for protein intake.

Another change in the new dietary guidelines is a recommendation to include both animal and plant protein sources.

The Scientific Advisory Committee had originally recommended prioritizing plant-based proteins over animal proteins, citing studies that found eating a diet high in plant proteins predicts better heart health in the future.

However, this recommendation was rejected in the new dietary guidelines. The authors of the accompanying scientific foundation report wrote that animal proteins provide a more complete nutrient profile.

Dr. Cate Shanahan, family physician, bestselling author, and Honorary Lecturer in Nutrition and Metabolism at De Montfort University, who was not involved in developing the newest dietary guidelines, said animal proteins typically contain all essential amino acids. By contrast, plant proteins do not have the same well-balanced ratio of essential amino acids and often contain antinutrients that can make nutrient absorption more difficult.

3. Recommendations on Fat

While the new guidelines keep the previous recommendations of a saturated fat limit at less than 10 percent, they recommend eating full-fat dairy as opposed to low-fat, and also give butter and beef tallow as potential cooking options.

There is one caveat. The dietary advice on animal proteins, dairy, and fat would cause people to easily exceed the 10 percent saturated fat limit, Alice Lichtenstein, distinguished professor and professor of nutrition science and policy at Tufts University, told The Epoch Times.

“This is weird that they kept the number, but then told you to go ahead and eat the sources that are higher in saturated fat,” Gardner said.

Gardner explained that the long-standing saturated fat limit of 10 percent is meant to give people a range.

“10 percent is sort of a reasonable range,” he said. “Is it the case that 11 is bad and 9 is even better? No one has the data that can show that level of specificity.”

Keeping the 10 percent saturated fat limit would also mean that schools, universities, hospitals, nursing homes, and prisons that rely on federal funding would not be able to change their meal menus as they still would need to meet the target, Shanahan said.

Limiting saturated fat intake is the longtime consensus for cardiovascular health.

This consensus was challenged in the scientific report accompanying the dietary guidelines.

Dating from the 1960s, studies including the Oslo Diet-Heart Study, the Los Angeles Veterans Administration Diet Study, and the Finnish Mental Hospital Study, concluded that reducing saturated fats and replacing them with plant oils such as soybean and corn led to improvements in cholesterol levels and reduced cardiovascular events.

In recent decades, however, some of these foundational studies have been dissected for their flaws.

For example, the outcomes in women who participated in the Finnish Mental Hospital Study did not reach statistical significance.

The Oslo Diet-Heart Study was also scrutinized, with researchers and journalists noting that the higher rate of cardiovascular events in the control group who consumed a high saturated fat diet could also be attributed to their intake of margarine and hydrogenated fish oils.

Cochrane Reviews, recognized as the gold standard in research, finds that reducing saturated fat reduces the risk of a cardiovascular event by 17 percent but does not affect overall mortality.

However, the exact health effects of saturated fat are still under debate.

Authors of the dietary guidelines acknowledged there’s an evidence gap on saturated fat, and say that more research is needed to determine the type of dietary fats best for long-term health.

4. First Time Not Recommending Seed Oils

For cooking, the new dietary guidelines recommend oils and fats such as olive oil, butter, or beef tallow. The guidelines do not include vegetable oils such as soybean oil and corn oil as an option, contrary to past recommendations.

In the supplemental report to the guidelines, authors wrote that the scientific reason to recommend eating seed oils like soybean, corn, canola, and cottonseed oil, is based on flawed science.

They added that seed oils have more polyunsaturated fats. While these fats help to reduce cholesterol levels, they are also more prone to oxidation when heated, and this can be harmful to people with metabolic disease.

Additionally, another common concern about seed oils is that they undergo extensive processing to make them shelf-stable and neutral in flavor.

However, since verbiage in the dietary guidelines did not explicitly restrict seed oils, a section in the guidelines on cooking oils raised grievances with experts.

The guidelines said that “when cooking with or adding fats to meals, prioritize oils with essential fatty acids, such as olive oil. Other options can include butter or beef tallow.”

Lichtenstein said that the recommendation indicates a disconnect between what is termed healthy fats and those containing essential fatty acids, since olive oil, butter, and beef tallow are low in essential fatty acids of linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acids when compared to more common sources of cooking oil like soybean and canola oil.

Shanahan said that she interpreted the section to mean that of the healthy fats available, olive oil, butter, and beef tallow are suitable options for cooking.

Scientists who contributed to the scientific foundation report on the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans on the sections for proteins, saturated fats, and seed oils all disclosed receiving funding or honoraria from the cattle and dairy industries.

Emily G. Hilliard, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services press secretary, told The Epoch Times that a separate methodology expert set protocols for conducting research, ensuring that conclusions are based on evidence. Scientists then followed the established protocols when researching and writing their reports. All reports were internally checked and peer-reviewed by outside experts with no conflicts of interest.

Takeaways

Regardless of the noise, the core of the new guidelines is to go back to real food and common-sense healthy eating, Du-Skabrin said.

People’s preference is still leaning toward whole foods, but due to various lifestyle reasons and convenience, they are choosing processed foods.

Gardner said that to fully reduce processed food intake, only changing the language is not enough—programs should be in place to incentivize farmers and the industry to produce healthier foods.

“It’s been a complaint of every dietary guidelines for the past 50 years, that there wasn’t enough requirement for the food industry to follow them, they’re guidelines, they’re aspirational, but it has to be followed up,” Gardner said.

The article was updated with comments from Emily Hilliard.