Patients with persistent Lyme symptoms face medical limbo as federal officials and researchers debate causes, treatment, and what to call the condition.

“Like a human hockey puck”—that’s how Nikki Schultek describes a year spent ricocheting between specialists in Connecticut, each focused on one piece of her deteriorating health—bladder pain, neurological symptoms, joint pain—while missing the whole picture.

“I really don’t fault the clinicians,” she told The Epoch Times. “The training hones them to be experts in a domain.”

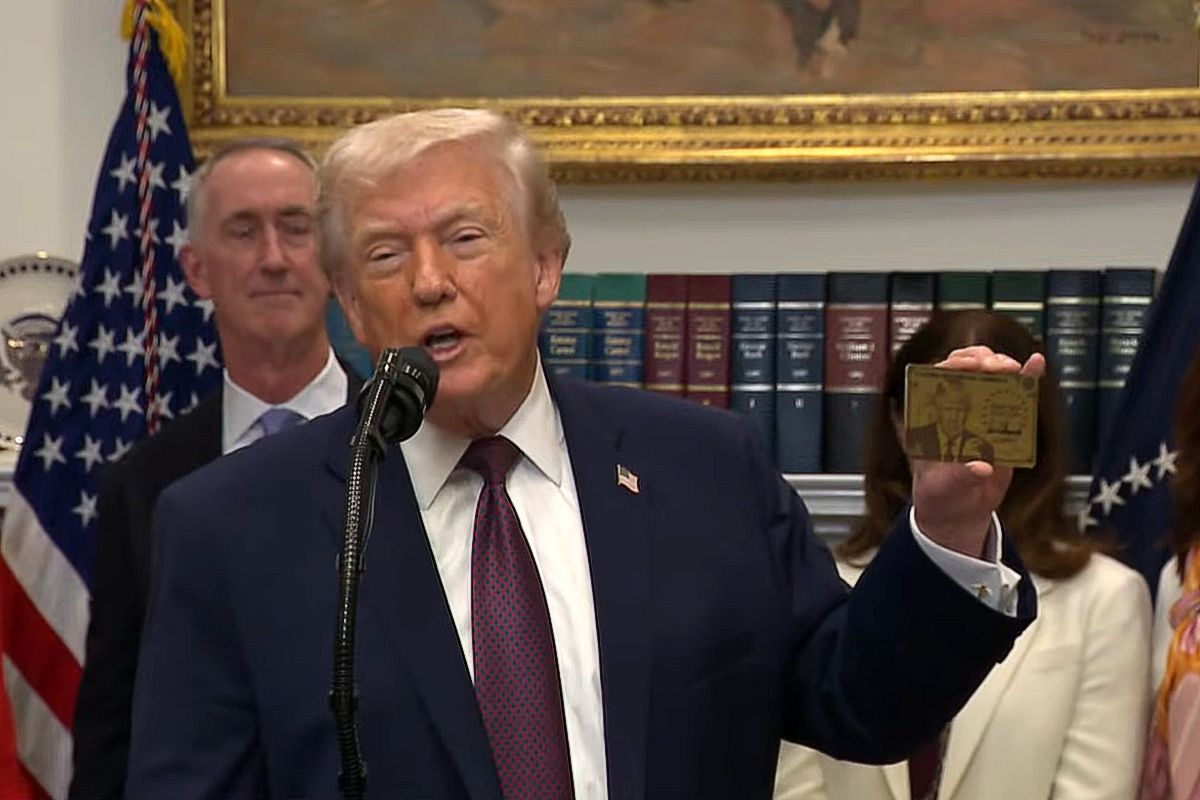

After her odyssey of misdiagnoses, Schultek finally received a correct diagnosis of Lyme disease. However, her experience navigating a fragmented health care system brought her to Washington on Dec. 15, where Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. convened a rare federal roundtable addressing what he called long-standing failures in how the disease is diagnosed, studied, and treated.

“Lyme disease is an example of a chronic disease that has long been dismissed, with patients receiving inadequate care,” Kennedy said at the event. “I want to announce that the gaslighting of Lyme patients is over.”

The Medical Divide

Schultek’s story echoes those of many patients whose months—or years—of fatigue, pain, neurological symptoms, and cognitive problems, after undergoing a battery of tests, are eventually traced back to that one tick bite that infected them with Lyme disease.

Persistent symptoms from Lyme disease are both difficult to diagnose and treat, in part because health agencies, mainstream medicine, researchers, and patients disagree about what is causing the debilitating constellation of symptoms.

The roundtable brought together patients, clinicians, researchers, and advocates to discuss what many describe as long-standing failures in how Lyme disease is diagnosed, studied, and treated. At stake is not just terminology, but access to care.

Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is spread through deer tick bites, most commonly in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and upper Midwest. Early symptoms can include fever, headache, and a characteristic rash, and around 90 percent of cases are successfully treated with a few weeks of antibiotics.

However, for about 10 percent of patients, like Schultek, symptoms such as fatigue, joint and muscle pain, and cognitive difficulties persist after antibiotic therapy.

“The cause of this is poorly understood,” Durland Fish, a professor emeritus of epidemiology at Yale School of Public Health who attended the roundtable, told The Epoch Times in an email. “But similar phenomena occur with other conditions, such as long COVID and chronic fatigue syndrome.”

The medical divide occurs here: Mainstream medicine, including federal health agencies, refers to persistent symptoms after treatment as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, or PTLDS, believing the symptoms are caused by lasting damage or an immune reaction to the initial infection.

For this reason, these institutions discourage the use of the term “chronic Lyme disease,” which implies that Borrelia bugdorferi bacteria remain in the body. They also discourage long-term antibiotic treatment for these patients, citing the risk of serious side effects.

“Chronic Lyme disease usually presumes that infection persists after therapy,” Fish said.

However, patients with persistent symptoms often prefer the term “chronic Lyme,” as they believe it better captures the ongoing nature of their illness. Many also developed symptoms without ever being treated for acute Lyme infection, making the PTLDS label less applicable to their experience.

Some are also open to the possibility of a persistent Lyme infection, noting that their symptoms improve temporarily with antibiotics.

“The central misunderstanding is the false assumption that persistent symptoms reflect a single, uniform condition with a single explanation,” said Dr. Amy Offutt, a physician who treats patients with complex Lyme disease and serves on the board of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society, in an email to The Epoch Times.