The Department of Government Efficiency reports $160 billion in savings amid legal challenges and other opposition.

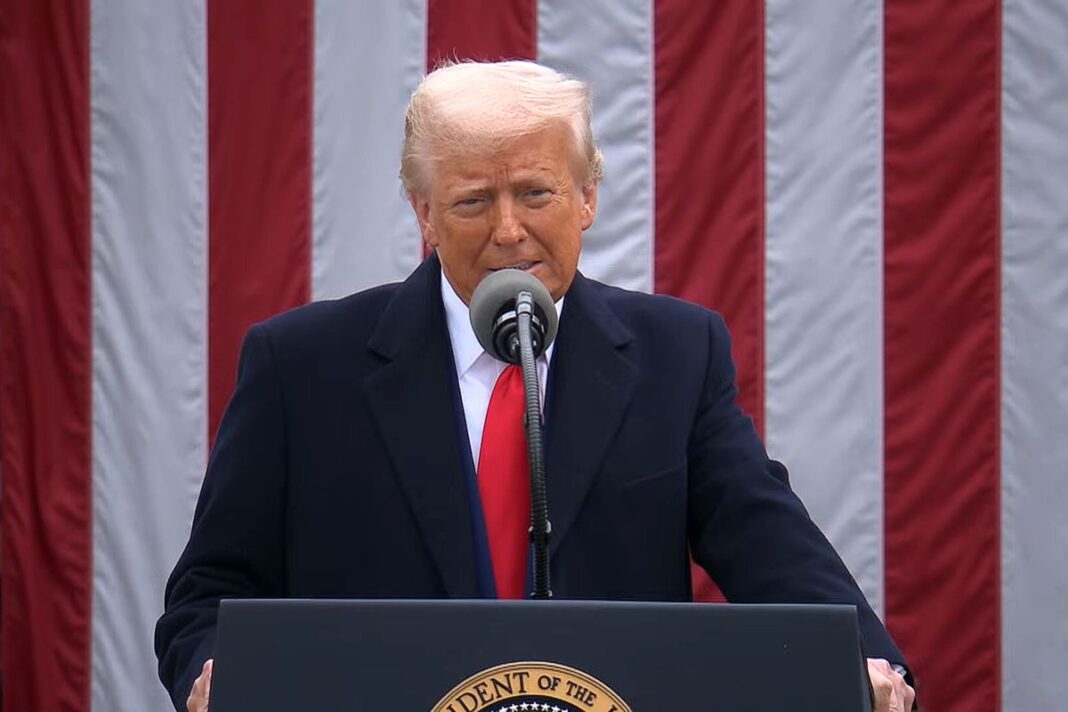

The second Trump administration has broken new ground in many areas. One big area is its Department of Government Efficiency, better known as DOGE.

Although DOGE cannot make cuts directly, it has led an effort across agencies to trim spending. Its stated focus has been to reduce waste, fraud, and abuse, as well as to modernize government technology.

Republicans have celebrated the time-limited initiative, which sunsets on July 4, 2026. So have some observers in Washington.

Democrats in Congress have questioned the scope of DOGE-inspired cuts and the organization’s access to sensitive data. DOGE has faced obstacles from the judiciary, too.

DOGE’s website reports to have identified $160 billion in savings so far. Here are key things to know about DOGE after its first 100 days.

DOGE’s Origins, Structure

Tesla CEO Musk was a top financial supporter of President Donald Trump’s 2024 candidacy. In August 2024, he suggested to Trump that he could lead a government efficiency commission. Trump pitched the idea publicly in early September, months before Election Day.

Trump formally announced the plan a week after the Nov. 4 election, tapping Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy to co-lead the effort. On Jan. 20, a DOGE spokesperson confirmed Ramaswamy would not be involved.

The president’s Jan. 20 executive order establishing DOGE renamed the U.S. Digital Service as the U.S. DOGE Service and placed it within the Executive Office of the President.

Amy Gleason, who served in the U.S. Digital Service during Trump’s first term, is the acting administrator of the U.S. DOGE Service.

The president’s Jan. 20 order instructed agency heads to create DOGE teams with at least four members, including an engineer, a team lead, and an attorney.

A February executive order directed agency heads to work with DOGE in identifying regulations seen as unconstitutional, costly, or otherwise questionable. Another order initiated similar coordination on contracting, grants, travel, credit cards, real property, and leases as part of a DOGE cost-efficiency initiative.

By Nathan Worcester and Lawrence Wilson