A COVID-19-era stimulus package caused Obamacare enrollment to skyrocket but increased dependency and fraud, further destabilizing the health insurance market.

Congress responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by passing the American Rescue Plan Act in early 2021. This $1.9 trillion spending bill was intended to provide relief and spark an economic recovery.

Among other provisions, the law expanded the availability of government-subsidized health care through the Obamacare Marketplace to help low- to middle-income people maintain health coverage until the economy normalized.

The measure brought millions of middle-class Americans into Obamacare, but had the unintended consequence of making many of them dependent on government aid.

The law also introduced temporary, enhanced subsidies, which raised Obamacare premiums, some observers say.

Though the enhanced subsidies expired on Dec. 31, 2025, Congress continues to debate their possible reinstatement.

Expanded Enrollment

Obamacare was created for people caught in the gap between Medicaid coverage and employer-sponsored health insurance.

The program provides income-based premium tax credits, which are subsidies paid directly to insurance companies, for people whose incomes are on the poverty line and up to four times above the poverty line (between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level).

People earning less than—or in some states, up to 138 percent of—the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid. Obamacare offers help for people earning up to four times that amount, up to $62,600 per year or $106,600 for a family of three, based on the current federal poverty level.

During the pandemic, Congress created subsidies that had no income cap. These enhanced subsidies also lowered enrollees’ affordability cap—the maximum amount a customer would pay out of pocket for a monthly premium.

Under the enhanced subsidies, introduced in 2021, no enrollee would spend more than 8.5 percent of their monthly income on premiums. Some would pay no more than 6 percent, others 4 percent or 2 percent, and some would pay nothing.

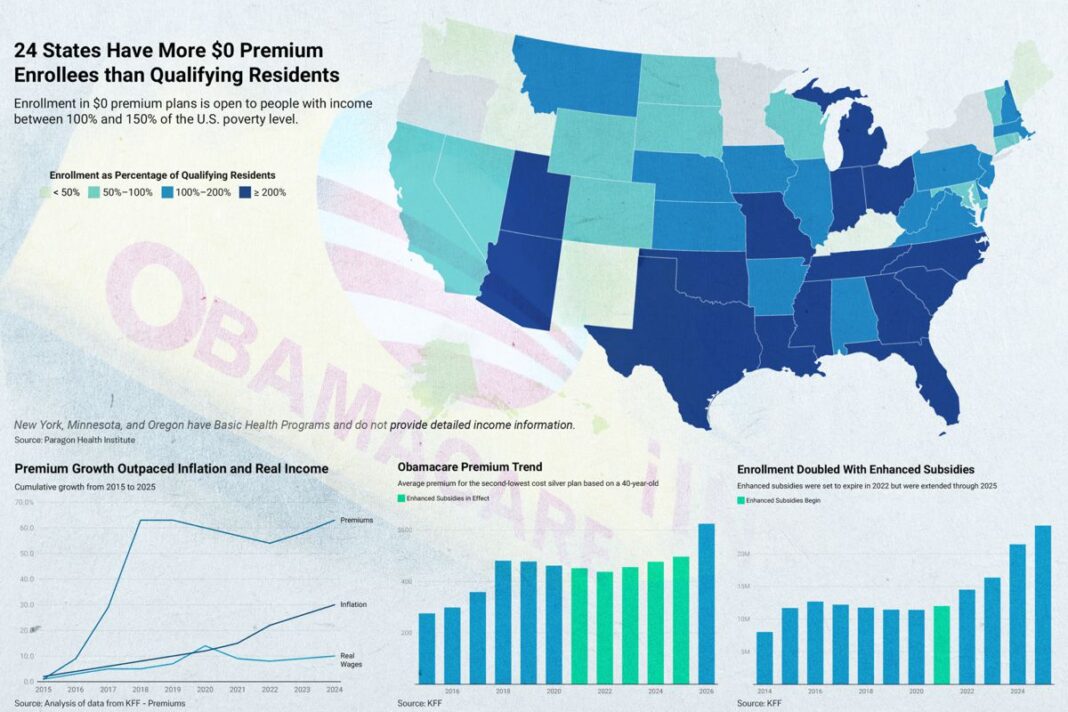

Enrollment boomed, jumping from 11.4 million to 14.5 million in two years. By 2025, enrollment had doubled from its pre-pandemic level, topping 24 million, according to data from health research organization KFF.

The enhanced subsidies were set to expire in 2022, allowing just enough time to get people back to work.

But when the pandemic ended, the enhanced subsidies remained.

Premiums Increased, Wages Didn’t

Health insurance premiums increased dramatically during Obamacare’s first five years. The average individual premium for a 40-year-old went up at least 75 percent, according to data reported by KFF.

Prices soared in commercial markets, too, where the cost of individual premiums rose about 120 percent from 2013 to 2019, according to The Heritage Foundation.

Obamacare prices leveled out before the pandemic hit and from 2020 to 2022, which includes the first two years of enhanced subsidies, prices dropped 5 percent, according to data reported by KFF.

But in 2022, the year the subsidies were set to end, inflation was on the rise, peaking at more than 9 percent by midyear, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Economists broadly agree that this was an unintended consequence of American Rescue Plan spending. The rising prices were “the product of easy fiscal and monetary policies, excess savings accumulated during the pandemic, and the reopening of locked-down economies,” Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, wrote in a co-authored assessment for Brookings.

Congress responded by spending even more money. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022, would pump another $1.2 trillion into the economy within a decade, the Cato Institute estimated. That included a three-year extension of the enhanced subsidies.

Obamacare premiums shot back up, according to data reported by KFF, rising more than 13 percent in three years.

Economic and policy researcher Cynthia Cox for KFF pointed to a number of factors driving the recent rise in premiums, including increased hospital costs, the rising popularity of expensive new drugs such as Ozempic, and the use of tariffs.

Many observers also cite the enhanced subsidies themselves as a driver of the problem they were created to address.

“The [Affordable Care Act] subsidy structure is itself inflationary—driving up health care prices and total premiums,” said Mark Howell and Brian Blase of the think tank Paragon Health Institute. “As Congress considers the future of the COVID Credits . . . it must confront the reality that the [Affordable Care Act] made coverage far less affordable.”

That reality was largely hidden from many who received the enhanced subsidies because their out-of-pocket premium payments were capped based on income. Price hikes above that cap were paid by taxpayers, which meant the enhanced subsidies were now even more important for people with modest incomes.

Meanwhile, the real wages of American workers were not keeping pace with the price of consumer goods, let alone the skyrocketing cost of health insurance.

Around that time, Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) commented on the value of the enhanced subsidies to members of his congressional district. “Without the Inflation Reduction Act, the average premium for these individuals would have increased by 76 percent, to $1,430, in 2023,” he said in a statement.

By 2025, the year the enhanced subsidies were again scheduled to expire, Obamacare premiums were at their highest point ever. Health insurers realized that, without the additional subsidies, healthier enrollees would drop their coverage in 2026, leaving a smaller, more expensive pool of people to insure, according to the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker.

Insurers responded with premium increases ranging from 10 percent to 59 percent, Peterson-KFF found, with the median being 18 percent.

Congressional Democrats argued that the enhanced subsidies had become essential and moved to make them permanent. Some Republicans agreed that a second extension of one to three years was needed.

After five years of premium increases largely paid for by federal taxpayers, both the insurers and the insured appear to have become dependent on the enhanced subsidies.

By Lawrence Wilson and Sylvia Xu