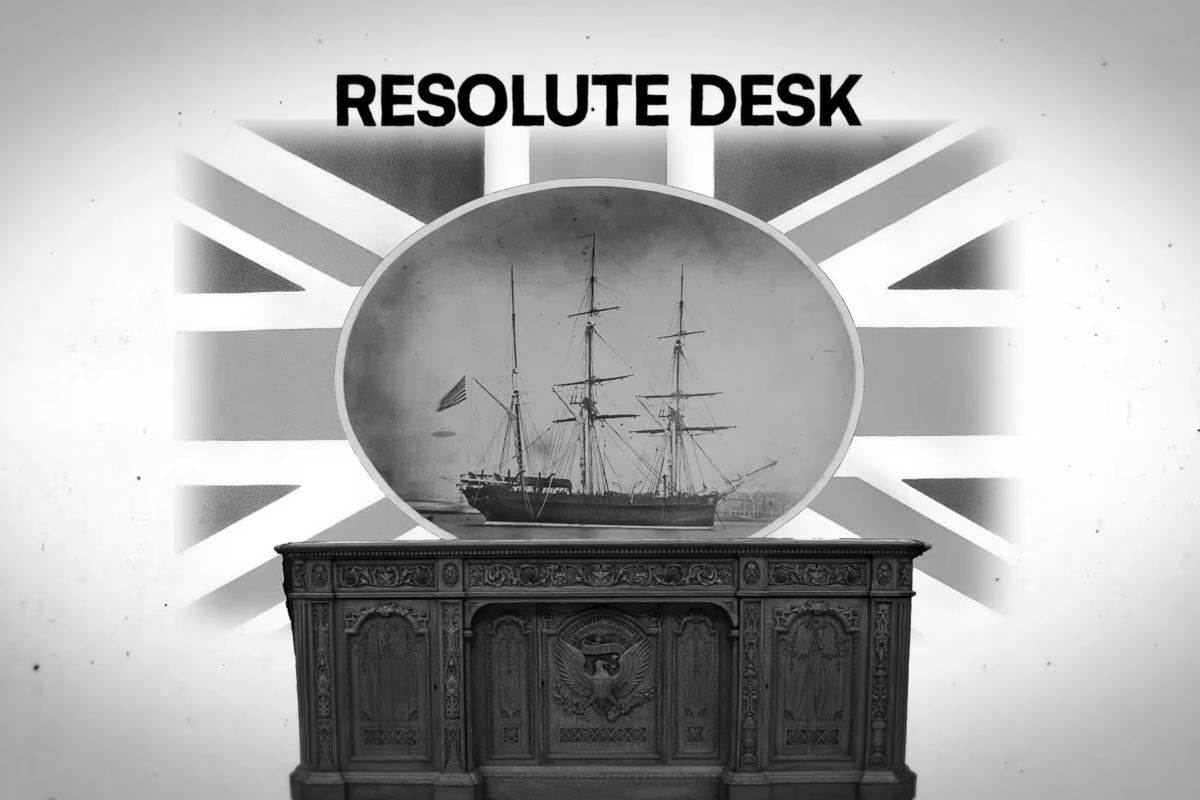

In the Oval Office once sat the Resolute Desk. A gift from Queen Victoria to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880. This piece of furniture may be relied on to bear the weight of the momentous decisions US presidents must sometimes make, but not so much our elected leaders.

Unlike the desk, we don’t receive the same dependability and strength from our government. A government whose excess is ever and eternally profligate.

The desk was built from the oak timbers of the British Arctic exploration ship HMS Resolute, hence its name. It has been used by many US presidents including the last five. By comparison, modern government is built on pillars of ego and self-enrichment, completely unsuited to supporting the weight of our nation.

Resolute means to be “firm or determined”. Firm and determined describes many political figures, but not the political process. That process is less solid, more gelatinous, and malleable than befits its necessity.

A resolution is defined “as a firm decision to do something”.

Our history is replete with substantive congressional achievements such as the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, Civil Rights Act of 1964, Clean Air Act of 1970, Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 and the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996.

Today, the only resolute aspect of government is spending and there is no sign that commitment is weakening. More recent bills of note are far from firm or determined such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010 and Biden’s euphonious Build Back Better, both of which are blights on the populace and our economy.

President Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill can’t yet be judged, but without substantive cost-cutting actions by the administration, odds are it may also be a debt increasing behemoth.

The recent shutdown is proof positive that the governing process is as irresolute as it has ever been.

Both sides use government shutdowns to hold hostage the other in a wacky game of Russian roulette. A game in which instead of one bullet there are none. Each side standing firm, sort of, on the principle of political gain.

Most recently, the Republicans proposed a continuing resolution that would fund the government for two months while adding $2 trillion dollars to the deficit, while the Democrats went the GOP one better in terms of trillions, seeking a CR that heaped $3 trillion on the debt.

A 42-day shutdown motivated by two parties, both of whom see debt as our destiny, not as our destruction.

Their solution? No solution, just a $2 trillion dollar debt increase and a trophy from hell.

A continuing resolution (CR) provides temporary funding to keep the federal government operating when regular appropriations bills have not been passed by the start of the fiscal year. Instead of passing “clean” appropriations bills to fund government, they choose politics over pragmatism, power over people.

CRs are being used by both parties in a grotesque game of “Chicken”. As both sides are blind, neither can see the headlights that portend their deaths. So comfortable are they with government by CRs, we’ve had at least one enacted in every fiscal year since 1977 and 139 since 1998.

In the five decades since the passage of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, Congress has passed all its required appropriations measures on time on only four occasions: fiscal 1977, 1989, 1995 and 1997.

Where there is no will, there is no way.

The very same people who find ending daylight savings time and making English the nation’s official language objects of such complexity as to be impossible, also can’t pass a simple budget.

Congress has become incapable of fulfilling their primary priority, not because of the difficulty in reaching consensus, but because they don’t want to. Ironically, this occurs in a situation where there is broad agreement on one thing: growing the debt.

Think about that. Two parties who fling the poo of their partisan rhetoric at one another like monkeys in a zoo and yet act as one when it comes to spending money the country does not have. Sadly, the deficit is the only thing on which the two sides agree.

We need a government that lives within its means, is laser-focused on debt reduction and whose appetite for our hard-earned money is limited by the lap band of baseline budgeting and a strict diet of budget reductions.

Until that happens, we must be resolute in our determination to reduce the size and scope of government. If we don’t, all we’ll have is a desk whose name is the antithesis of our government upon which to write our doom.

Stephen Piccirillo 2025