Let’s take a look at some of the inner workings of a centuries-old trade mechanism.

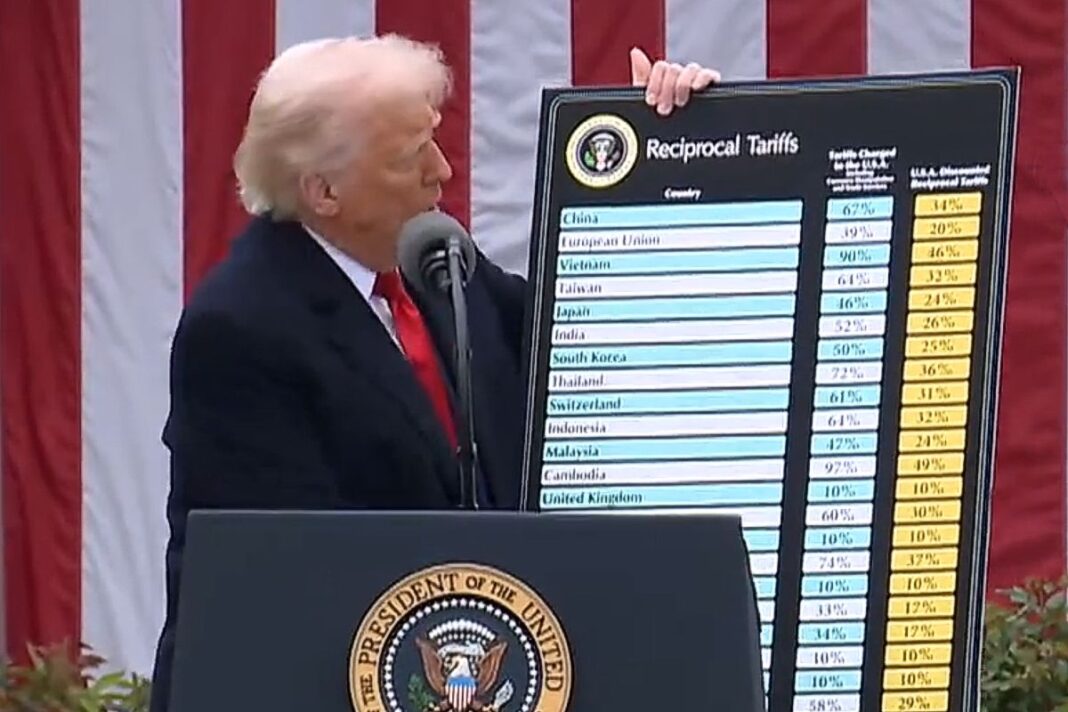

Since President Donald Trump’s return to the White House, tariffs have been the centerpiece of the administration’s economic agenda.

In addition to his global sweeping tariff plans announced on April 2, the president has also imposed levies on automobiles, aluminum, copper, and steel.

Rebalancing global trade—turning the United States into a producer again and other nations into consumers—has been one of the core objectives behind these far-reaching levies.

Reversing trade deficits, rectifying unfair trade practices, and generating revenue for the federal government are other aims of the president’s tariff agenda.

But what are some of the inner workings of a centuries-old trade mechanism?

Why Tariffs?

For centuries, governments have employed tariff measures for economic, fiscal, and political reasons.

“I always say ’tariffs’ is the most beautiful word to me in the dictionary,” the president said shortly after his inauguration in January. “Because tariffs are going to make us rich … It’s going to bring our country’s businesses back that left us.”

Many of his predecessors would agree with his position.

The Tariff of 1789 was the first significant law approved by Congress, intended to fund the government and shield emerging U.S. industries.

Since then, the White House and lawmakers have implemented a treasure trove of tariffs.

In 1890, the McKinley Tariff—touted by Rep. William McKinley and signed by President Benjamin Harrison—protected domestic manufacturers from foreign competition by raising import duties on tinplates and wool.

The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which economists say exacerbated the Great Depression, raised tariffs on more than 20,000 imported goods.

The Trade Act of 1974 introduced Section 301, which has been regularly used by presidents to combat unfair trade practices.

Governments, at home and abroad, routinely wield the tariff as a protectionist weapon. But then, who pays?

Dollars and Cents of Tariffs

Tariffs are a tax paid by importers, not foreign governments.

If a U.S. business is purchasing smartphones, televisions, or automobiles from a foreign market—such as Indonesia or Vietnam—the company will pay the tariff, not the Indonesian or Vietnamese governments.

One of the reasons economists fear that tariffs will rekindle the inflation flame is that businesses could pass the tariff-related costs onto consumers through higher prices.

At the same time, businesses could also cushion the financial blows by absorbing the costs, stockpiling inventories—like how many importers rushed their purchases of foreign goods ahead of the tariffs—or delaying price increases.

So far, despite the plethora of industry surveys suggesting companies plan to make shoppers bear at least some of the costs, the data signals have been mixed.

In the June Consumer Price Index (CPI) report, for example, tariff-sensitive sectors have produced different trajectories.

The indexes for new vehicles and used cars and trucks declined 0.3 percent and 0.7 percent, respectively.

Meanwhile, the apparel index surged 0.4 percent last month.

Additionally, according to the CPI report, television prices fell 0.1 percent, smartphones remained unchanged, and appliance inflation increased 1.9 percent.

“The details show that there was some scattered evidence of early tariff impacts on some goods components—mainly fresh fruit & vegetables, household appliances, toys, clothing, and sporting goods, but this was offset to a large extent by softness in the all-important shelter component,” ING economists said in a July 15 note.

Shelter accounts for about 40 percent of the core CPI basket.

Meanwhile, in addition to importers paying the levies, foreign firms can also absorb the higher expense by sacrificing profit margins to remain competitive in the United States.

New data indicate that Japanese automakers, for instance, are absorbing tariff-related costs in the form of lower prices.

In June, auto export prices to the United States declined 20 percent per unit year over year.

At the same time, the volume of car shipments increased by more than 3 percent.

Tariffs can adversely impact overseas markets by encouraging importers to seek alternative suppliers, either domestically or in other regions with lower tariffs.

As a result, foreign companies may be compelled to reduce prices to maintain market share—Japanese carmakers account for about 30 percent of the U.S. auto market—and retain their U.S. customer base.

Does this mean the U.S. economy has cut off the tariff-inflation connection?

“The pass-through so far has been relatively modest, but that doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods yet,” Gurpreet Garewal, macro strategist in Goldman Sachs Asset Management, said in the bank’s recent episode of the podcast “The Markets.”

By Andrew Moran