Sure, they are unpopular, but that’s because they are misunderstood – they are in fact part of a larger, more involved scheme which could reset America’s global economic relations.

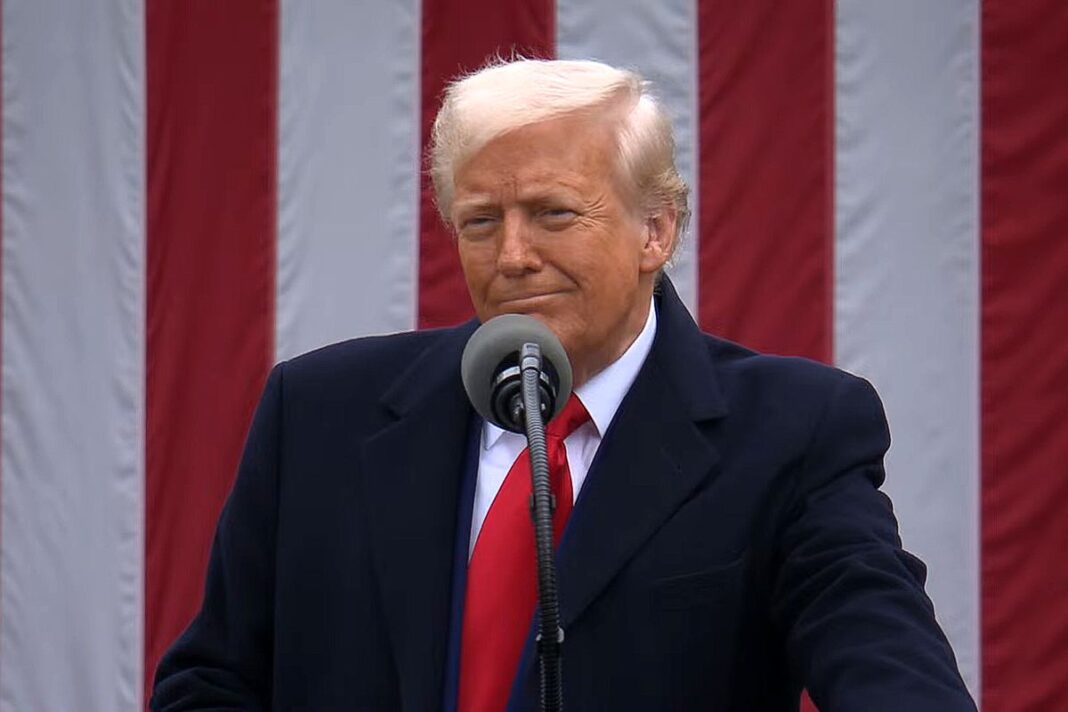

It is not my intention here to be an apologist for Donald Trump’s tariffs. But I do take issue with the manner in which any discussion about them typically occurs. They are often summarily dismissed with a rather smug remark of derision with little regard for them in a broader economic context, either domestically or globally.

If one is to understand the basis for Trump’s tariffs one must first understand how trade imbalances occur and why.

Global trade deficits and surpluses are the result of uneven allocation between national savings and investment. Countries like China, Germany and Japan tend to save capital rather than invest it domestically – as a result some of that capital flows abroad – creating a trade surplus.

In the US, the economics are just the opposite. America invests much more than it saves, and the reduced savings is supplemented by capital flows from abroad – producing a trade deficit.

These trade imbalances have been occurring for decades. Export-oriented countries (e.g. China, Germany, Japan) have pursued policies that siphon income away from consumers – which tend to spend – toward businesses and the government, which tend to save. The effect is an increase in national savings. Since not all the savings can be invested domestically, the excess capital flows abroad. Each year about $1.2 trillion in foreign capital reaches the US.

In the short term, this isn’t necessarily a problem. The US economy remains vibrant, strong. But beneath the surface, the reality of expansive federal debt, recurring trade deficits and rising interest rates are a precarious mix for the US economy. As government borrowing to finance budget deficits becomes more expensive, it becomes progressively more of a burden to service that debt – it’s a drag on GDP.

In addition, China, a major trading partner with the US, only recently increased its commitment towards stimulating domestic consumption – for decades it has looked abroad. Moreover, the EU’s economic issues are driving even more capital into the US economy. This only makes the imbalance worse.

American presidents may constitutionally serve only two four-year terms, and Trump is in his second term. The president knows time is not on his side. He knows his current slim Republican majority in both houses of Congress could shift to a minority status in the next midterm elections. Hence, if he’s going to act to achieve something for the American economy (and his legacy), it has to start now.

Trump’s Dilemma

The question for Trump is: How can the US reduce trade deficits and increase the savings rate while keeping interest rates low – especially long-term Treasuries? There are several ways to achieve the above, but most are neither easy nor quickly implemented.

- Cut taxes for businesses and invest in manufacturing

- Reduce government spending

- Limit capital inflows

- Impose tariffs.

Clearly, Trump has opted for tariffs that are (at least politically) the easiest to implement and do so immediately.

For Trump to achieve what he wants for America, tariffs alone will not do the job. A broader scheme will likely include portions of all four approaches just mentioned.

While there is room for criticism with Trump’s implementation of his tariffs, one must look at the larger picture to fully understand what’s going on.

An often-cited critique is that attempting to bring into balance every bilateral trade agreement is unreasonable. While this is a valid critique, that is not what the president is attempting to achieve.

Trump isn’t necessarily trying to just balance trade; he’s actually attempting to negotiate. The US market is pivotal to a significant number of countries; thus, Trump seems to be using the need for access as a fulcrum to negotiate better terms for America. The tariffs are not designed to be punitive – but to induce more meaningful negotiations – rather than just accept the decades-old status quo of trade deficits for America.

Some of Trump’s critics warn that tariffs could lead to a global economic downturn. They often cite the 1930s Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which many fault for worsening the Great Depression. But that argument stems from a poor understanding of the historical record. In the 1930s, America was experiencing a trade surplus – we were consuming less than we were investing – tariffs only exacerbated the problem. Today, the US problem is just the converse.

Certainly, one cannot exclude the possibility that the tariffs won’t work. Essentially, the duration of the trade war will tell the tale. It is likely (as we are seeing this already) that a good measure of the tariffs will ultimately be rolled back as part of newly negotiated agreements. Moreover, even if there is a protracted trade war, the “economic pain” will be felt more by surplus countries like China, Germany and Japan. The US will feel the impact least and last.

The elephant in the room is inflation

The greatest immediate risk is “too much money chasing too few goods.” Trump argues that greater domestic production will quickly increase to meet demand, keeping prices under control. One should accept that argument with a healthy measure of skepticism. Increasing domestic production takes time to implement. Wholesale and retail price increases happen much faster.

Trump is running a measured risk – some call it gambling. Tariffs are relatively inefficient. That’s why so many economists tend to criticize their use.

But Donald Trump is attempting to correct something beyond just trade imbalances. He wants to reset the economics of the US – and by association that of the world — to the advantage of America. And he’s using tariffs to jump start the process.

The approach is both dramatic and fraught with peril. But it’s not crazy – it’s a measured gamble that looks like it might just work.