A judge’s ruling that some payments to insurers were illegal set off a cost spiral.

Insurance premiums are just one piece of the health care affordability puzzle for many Americans. Out-of-pocket expenses, which are less predictable, also impact the family budget.

Those out-of-pocket costs for deductibles, copayments, and the like now average more than $1,600 a year per person. That’s on top of insurance premiums, which run about $27,000 for a family plan.

Obamacare aimed to help with both expenses—premiums and out-of-pocket costs—by providing federal subsidies for low-to-middle-class Americans. Both are based on household income as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

There are two kinds of subsidies, one to help with premiums and the other for out-of-pocket spending.

The first subsidies, called advance premium tax credits, are paid directly to insurance companies to reduce premium payments. These are open to people making up to about $62,600 per year, or around $107,000 for a family of three.

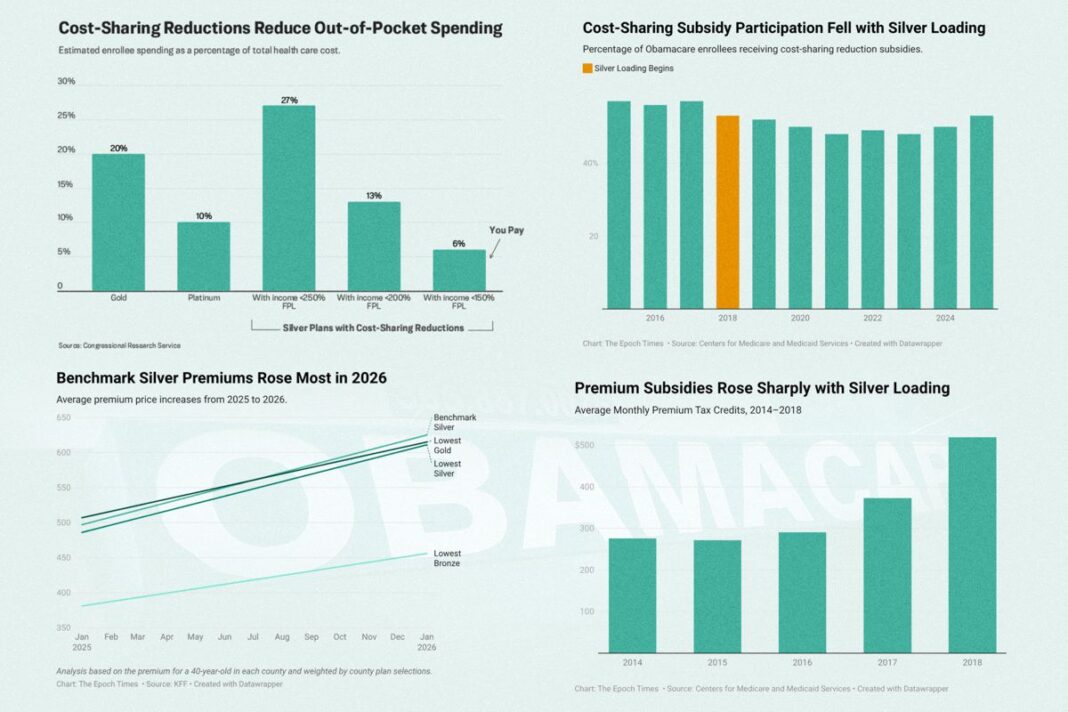

The second subsidies, called cost-sharing reductions, reduce the copayments, deductibles, and out-of-pocket maximums on certain insurance plans for people making a bit less, about $39,000 for an individual or some $66,600 for a family of three.

Together, these subsidies were supposed to make health insurance highly affordable for everyone.

Yet this plan, like some other provisions of the Affordable Care Act, had unforeseen consequences, due to 16 words from Article I of the U.S. Constitution: “No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”

Here’s how cost-sharing reductions, which were meant to save money, wound up costing insurers, consumers, and taxpayers even more money than before.

Silver Plans Only

People who qualify for cost-sharing reductions could see their spending on deductibles, copayments, and out-of-pocket maximums reduced up to 80 percent.

The only catch is that they must select a silver-tier insurance plan to get the benefit.

Obamacare offers four levels of plans: bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Bronze plans have the lowest premiums, but the deductibles, copayments, and out-of-pocket maximums are higher. Platinum plans have the highest premiums, but lower out-of-pocket requirements.

Silver plans are somewhere in the middle and are usually the most popular choice.

On average, customers with a silver plan would pay about 30 percent of their health costs out-of-pocket, not counting premiums. The insurance company would pay about 70 percent.

With cost-savings reductions, that ratio would change. The insurance company would pick up between 73 percent and 94 percent of the cost, leaving customers to pay as little as 6 percent of provider charges.

For some enrollees, a silver plan could leave them with lower out-of-pocket expenses than even a pricier platinum plan.