One in four new construction permits in California are for accessory dwelling units in backyards.

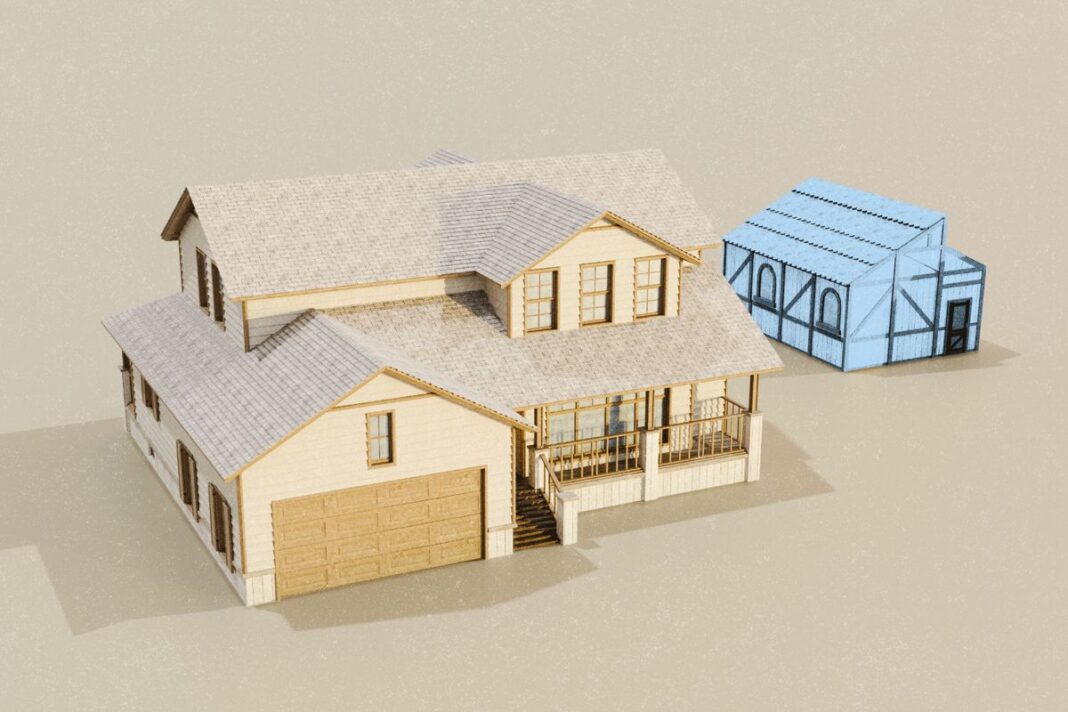

LOS ANGELES—For Sam Andreano, rental income from a detached accessory dwelling unit (ADU) in his backyard initially helped offset mortgage payments, and later provided a place for his son to land.

“[I] started out as just a regular homeowner,” said Andreano, a resident of Dana Point, Orange County, who began converting his detached garage into an ADU in 2019.

Researching and permitting took a few months, and total build-time was around eight months. He financed it with cash and a refinance. The entire investment, including all labor, materials, city and associated fees, came out to $165,000, and he rented the one-bedroom unit for $2,500 a month.

Now he’s working on a two-story ADU project that he intends to sell as a four-plex.

Amid soaring home prices and a housing crisis—which California leads, by some estimates, with a deficit of more than a million homes—accessory dwelling units (ADUs) now represent a significant and steadily increasing supply of overall housing construction in the Golden State.

A descendant of the post-War “granny flats” or “dowager cottages” intended to house aging relatives, at least half of contemporary ADUs are predestined for the rental market. Most are modest studios or one-bedrooms that can be built at a fraction of the cost of a traditional home, but still command market rate rents.

California issued 30,231 permits for ADUs in 2024, representing 26 percent of all new housing construction, according to statistics provided by the Department of Housing and Community Development.

While the rate of increase has fluctuated, data over the past decade show a steady year-over-year climb. After plateauing in 2019 and 2020 at under 13,000 units, the number jumped to more than 20,000 in 2021, a more than 60 percent increase.

This is largely due to a series of liberalizing state laws that have, over the past eight years, made it much easier for property owners to get projects approved in residential areas originally zoned for single-family homes.

To proponents, the boom is a bulwark against a worsening affordable housing crisis, even a corrective measure to decades of exclusionary zoning.

To critics, it overburdens infrastructure, threatens property values, degrades aesthetics, and represents an unprecedented loss of community control over residents’ quality of life.