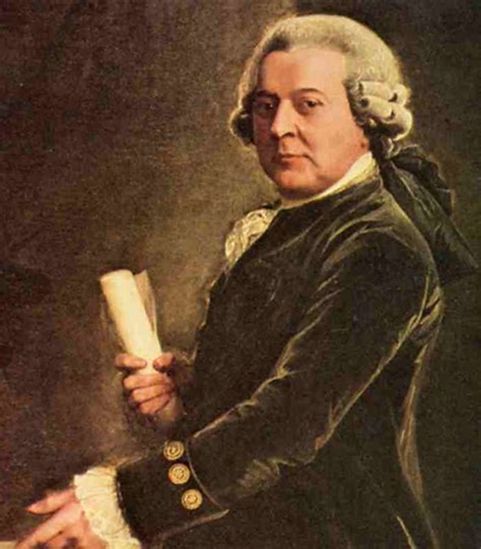

John Adams. Today the name brings to mind the feisty man portrayed by actor Paul Giamatti in the 2008 HBO miniseries, John Adams. In between Presidents Washington and Jefferson, short, blunt John Adams seems to be a forgotten part of history, arguably overshadowed by other great men of his time. He is very important not only in the history of the United States, but in his own right as well. Washington is the Father of his Country, Jefferson author of the Declaration of Independence, Madison Father of the Constitution; less-celebrated Founding Father John Adams has been called “Architect of the Revolution.”

The eldest of three boys born to his farmer and shoemaker father, John Adams came into the world on October 30, 1735 at Braintree, Massachusetts. Though an outdoor type of boy, he attended Latin school.

Later he explained how his father had instilled in him the meaning of hard work and the reward of diligence:

When I was a boy, I had to study the Latin grammar; but it was dull, and I hated it. . . . I studied the grammar, till I could bear it no longer; and going to my father, I told him I did not like study, and asked for some other employment. . . . He was quick in his answer. “Well, John, if Latin grammar does not suit you, you may try ditching; perhaps that will; my meadow yonder needs a ditch, and you may put by Latin and try that.” This seemed a delightful change, and to the meadow I went. But I soon found ditching harder than Latin, and the first forenoon was the longest I ever experienced. . . .That night I made some comparison between Latin grammar and ditching, but said not a word about it. I dug next forenoon, and wanted to return to Latin at dinner; but it was humiliating, and I could not do it. At night, toil conquered pride; and though it was one of the severest trials I ever had in my life, I told my father that, if he chose, I would go back to Latin grammar. He was glad of it; and if I have since gained any distinction, it has been owing to the two days’ labor in that abominable ditch.

After turning sixteen, Adams went to Harvard, still uncertain whether to become a surgeon or clergyman. Following his graduation in 1755 he taught school for three years in a one-room schoolhouse.

In 1759, as an established lawyer of nearly twenty-nine, John Adams decided to marry nineteen-year-old Abigail Smith, daughter of Rev. William Smith. Both parents disapproved of Abigail’s choice, and turned up their noses at Adams’s legal profession, especially when they learned his income would have to be supplemented by his farm. But the couple decided to marry, and asked her father to perform the ceremony. The Reverend’s text was a dubious “verse” from Luke, reading: “John came neither eating bread nor drinking wine and some say he has the devil in him.” Nevertheless, John and Abigail Adams remained married for fifty-four years, until her death. They had five children: Abigail (called “Nabby”), John Quincy (later President), Susanna (who died at age two), Charles (who died at age thirty, during his father’s presidency), and Thomas.

Adams’s first public office came in 1761 when he was elected surveyor of highways in Braintree. He had no surveying experience, but in his day, all male members of the community were expected to perform some sort of civic duty. Such was the beginning of a compelling statesman and President. Adams was outspoken early on, disavowing the Stamp Act of 1765—he and his cousin Samuel among the first to insist the colonies should seek independence. In fact, Adams drafted a set of instructions regarding the Stamp Act for a Braintree town meeting. These instructions declared the Act unconstitutional, and attacked the practice of the admiralty court to try offenders without a jury.

The next big event for Adams came in early fall of 1770 when he defended Captain Thomas Preston and several British soldiers who were being tried for murder. Earlier (March 5), in what was called the “Boston Massacre”, the soldiers had fired on a provocative mob; three colonists were killed, two others mortally wounded. Because the state of affairs between England and the colonies was coming to a boiling point, the trial was delayed for six months to allow tempers to cool. It was Adams, although far from sympathetic toward the British cause, who insisted these soldiers have a fair trial. So, he took this unpopular task and Captain Preston was acquitted. By now, Adams had become a successful lawyer with an office in Boston, his practice including two clerks. Despite his being offered attractive posts by the Crown, he declined these; for it was far from secret that Adams was opposed to the oppressive royal government. He was a leader of the independence movement: “All men are born free and independent, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property . . . .” The Boston Tea Party he considered “the grandest event which has ever happened since the controversy with Britain opened.” The colonies were soon plunged into war.

“Master of the law” John Adams took part in the Continental Congress, sitting on more committees and working harder than any other delegate. His boldness alarmed many of the members, as he was “sometimes outspoken to the point of rudeness” (Britannica), proposing bold measures to pave the way to independence. “People and nations are forged in the fires of adversity” he would remark. Indeed, this was no time to be worried about offending people. John Adams was never softspoken, nor did he try to be. “I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular,” he admitted.

In June 1776, when Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution in Congress calling for complete separation from Great Britain, this motion was quickly seconded by none other than John Adams.

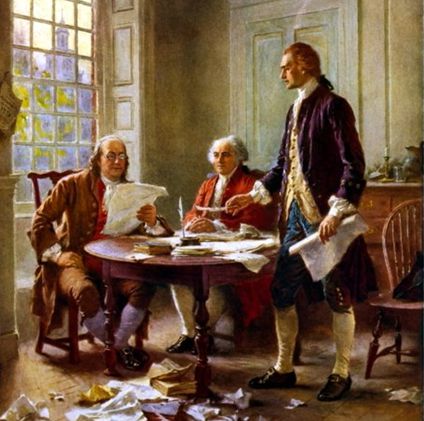

Adams was assigned to a committee of five men to draft this declaration of independence; he encouraged Thomas Jefferson to write it. When the declaration came to the floor, Adams energetically began “fighting fearlessly for every word of it,” as Jefferson gratefully recalled. “John Adams was the pillar of its support on the floor of Congress, its ablest advocate and defender against the multifarious

assaults it encountered.” Jefferson added, “He was not graceful, nor elegant, nor remarkably fluent; but he came out, occasionally, with a power of thought and expression that moved us from our seats.” On August 2, Adams dipped his quill in ink and signed the Declaration of Independence. This act did not merely put a signature on paper, it put a price on his head. If Adams were captured or the colonist lost the war, he would be hanged until unconscious, then revived, disemboweled, beheaded, cut into quarters, and boiled in oil. Such was the penalty for treason, of which each of the signers were aware. After the declaration was read to a crowd in Philadelphia, Adams wrote: “Three cheers rended the welkin [sky]. The battalions paraded on the common and gave us the feu de joie [firing of guns], notwithstanding the scarcity of powder. The bells rang all day and almost all night.”

“The science of government is my duty to study . . . . I must study politics and war, that my sons many have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy.” Having said this, Adams kept in mind John Quincy, Charles, and Thomas, and remained as active as ever in Congress, persuading the members to organize a Continental Army, next routing for George Washington’s appointment as commander-in-chief. “Burning with patriotic fire, strong-minded John Adams put oratory and law training to good use in the Revolutionary struggle,” beamed one biographer.

To John Adams, 1776 was an eventful year. He was appointed to the committee sent to confer with British Admiral Richard Howe who, following the Battle of Long Island, had proposed an informal peace conference. Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Edward Rutledge met with the admiral at British headquarters on Staten Island. But Howe would only receive them as “private gentlemen”, not as members of Congress. Nothing came of the meeting. John Adams’s next project was taking the initiative in convincing Congress that the war should be conducted with a respect for human rights. He wrote his wife: “I who am always made miserable by the misery of every sensible being, am obliged to hear continual accounts of the barbarities. . . committed by our enemies. . . . These accounts harrow me beyond description.” He felt Americans should pioneer in what he called “the policy of humanity”, including toward the enemy. He said, “I know of no policy, God is my witness, but this—piety, humanity and honesty is the best policy. Blasphemy, cruelty and villainy have prevailed and may again. But they won’t prevail against America, in this contest, because I find the more of them are employed, the less they succeed.” He was able to convince others in Congress of this; the critical period of the war saw leaders of the army adopting Adams’s policy.

In 1777, Adams found himself appointed as the third minister to France replacing Silas Deane, whose loyalty to the Revolution was waning. Though Adams had hoped to take his family with him, the dangerous voyage remained an obstacle. He compromised by taking eleven-year-old John Quincy. The small, slow ship was one the British hoped to capture, especially with Adams as a passenger. However, father and son landed safely in France in 1778, and arrived in Paris a month after, where Adams was received at Versailles by King Louis XVI. There he negotiated much-needed loans for the colonies. A year later he and John Quincy were back in Boston. No sooner had Adams touched American soil he was appointed minister plenipotentiary (i.e., officiating) to negotiate treaties of peace and commerce with Great Britain.

This was how most of the Revolutionary War was spent—on diplomatic missions, including his serving in France and Holland. In 1782, Adams was back in Paris as a peace commissioner, where he and Franklin were to join conversations with the British. Congress had instructed the Americans “ultimately to govern yourselves by the advice and opinion of the French ministry.” Adams distrusted the French and resented these orders. He nearly resigned. In the end, he simply chose to ignore the instructions instead. Adams’s partner, Dr. Franklin, felt at ease among the French: “Mr. Adams, on the other hand, who at the same time means our welfare and interest as much as I or any man can do, seems to think a little apparent stoutness, and a greater air of independence and boldness in our demands, will procure us more ample assistance.” Franklin fretted, “He thinks the French minister one of the greatest enemies of our country.” Adams, Franklin, and John Jay were finally able to sign the peace treaty with Great Britain in 1783. Shortly after this Adams departed for London.

Abigail Adams had long borne with “the cruel torture of separation” from her husband. Adams—the French perhaps having put him more than a little out of humor—wrote to her, fuming, “Come to Europe with Nabby as soon as possible. I cannot be happy nor tolerable without you.” Mrs. Adams and her nineteen-year-old daughter arrived in London in the summer of 1784, where they reunited with John Adams and the now seventeen-year-old John Quincy. The war had ended, but Adams’s service to his country had just begun.

To be continued. . .

Bibliography:

Adams, John, quoted in—Chapman, James A., ed. Handbook of Grammar and Composition, 5th ed. A Beka Book, 2002.

Aikman, Lonnelle. The Living White House. Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 1982.

Allison, Andrew M., Jay A. Parry, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real George Washington, 3rd ed. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Allison, Andrew M., M. Richard Maxfield, K. DeLynn Cook, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real Thomas Jefferson. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Allison, Andrew M., W. Cleon Skousen, and M. Richard Maxfield. The Real Benjamin Franklin. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Aronson, Steven M. L. Presidents: Fandex Family Field Guides. New York: Workman Publishing Co., Inc., 2016.

Athearn, Robert G. The American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States, Volume IV: A New Nation. New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1963.

Barton, David, ed. and trans. Wives of the Signers: The Women Behind the Declaration of Independence. WallBuilder Press, 2010.

Caroli, Betty Boyd. First Ladies. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Freidel, Frank. Our Country’s Presidents. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1966.

Hamburger, Kenneth E., Joseph R. Fischer, and Steven C. Gravlin. Why America is Free. Published by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1998.

Lengyel, Cornel Adam. Presidents of the U.S.A.: Profiles and Pictures. Bantam Books, 1961.

Lorant, Stefan. The Presidency. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952.

Lowman, Michael R. United States History: Heritage of Freedom, in Christian Perspective, 3rd ed. A Beka Book, 2015.

Mattern, David B., ed. James Madison’s “Advice to My Country.” University Press of Virginia, 1997.

Skousen, W. Cleon. The Making of America, 3rd ed., revised. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2007.

Taylor, Tim. The Book of Presidents. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1989 ed. S. v. “John Adams” by Robert A. East.