John Adams: Architect of the Revolution, Part 1

The war over, the young United States attempted to continue trading with the British. In 1785 John Adams presented his credentials to George III as the first official American minister to London. When he and Thomas Jefferson were introduced to the king at the royal court, Jefferson said “it was impossible for anything to be more ungracious than their notice of Mr. Adams and myself.”

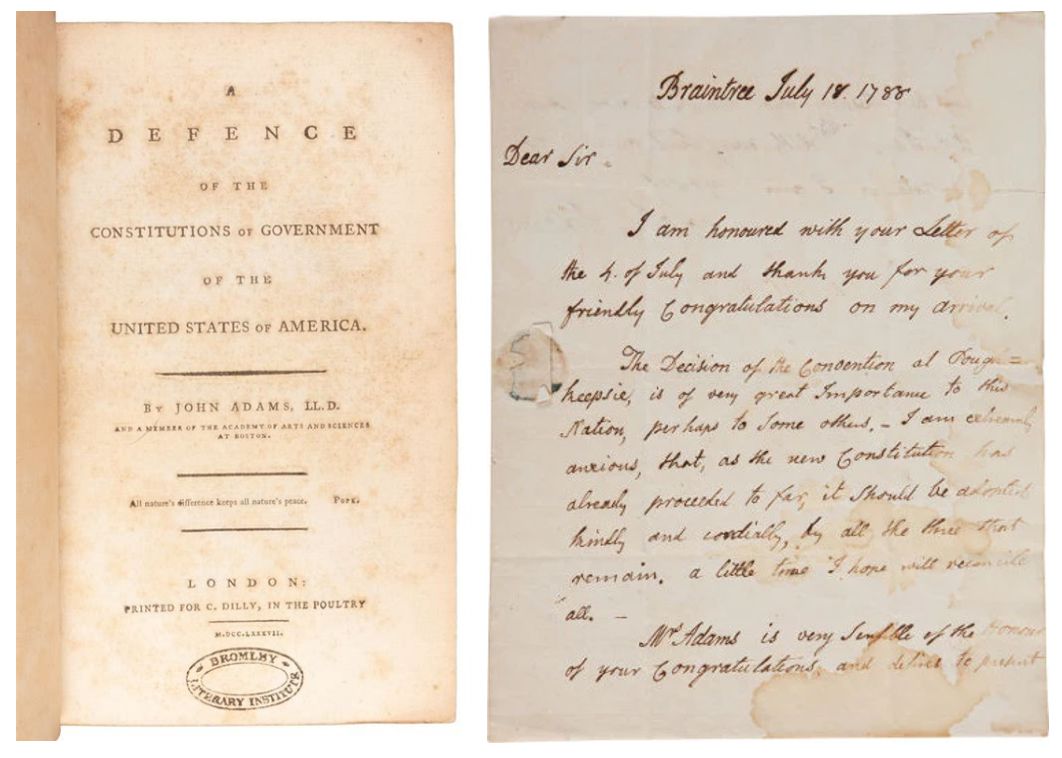

Absent from the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Adams was still able to make an important contribution by writing “A Defence [sic] of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America”, read and quoted by the delegates. Adams wrote an English friend that he hoped “to see rising in America an empire of liberty, and a prospect of two or three hundred millions of freemen, without one noble or one king among them.” If John Adams’s many years of foreign residence had taught him anything, it was to maintain a healthy distrust of the French while questioning the morals of the Europeans (Britannica). Unfortunately, his service as a diplomat gave many the impression he had been transformed into an aristocrat, later causing many to fail to vote for him as President in 1789, instead throwing their support to George Washington. Adams sailed for the United States in the spring of 1788, having been in Europe for over ten years. He had recently purchased a farm in Quincy, Massachusetts, but there was no time for getting settled: He was to become the nation’s first Vice President.

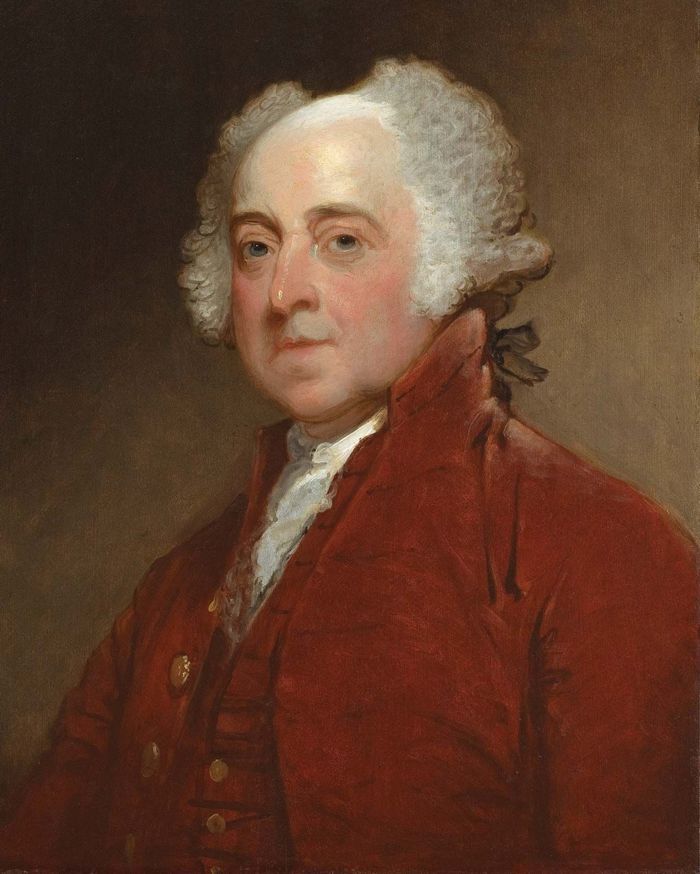

The Vice Presidency turned out to be something of a thorn in his side—”a mere mechanical tool to wind up the clock,” he called it. Adams suggested a title for the President, “His Most Gracious Highness, the President of the United States of America and Protector of Their Liberties,” which, Jefferson said, “was the most superlatively ridiculous thing I ever heard of.” Adams in turn was mockingly offered the title “His Rotundity,” suggestive of his stout figure. This was not all. Opponents of Washington’s administration intimidated by the President rejoiced over showering criticisms on Adams instead. “My country has in its wisdom,” Adams huffed, “contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived. And as I can do neither good nor evil, I must be borne away by others and meet the common fate.” Two terms was enough to try his patience. He felt his dynamic talents were being wasted.

Then came the election of 1796. The radical Hamiltonians were slurring John Adams as the “Duke of Braintree,” and though he was unpopular and distrusted, the Federalists nominated him for President. When the electoral votes were counted, Adams, as President of the Senate, announced himself the winner: “I declare that John Adams is elected President of the United States.” It was a close vote—71 to 68. His rival, Jefferson, became the Vice President.

Sixty-one-year-old Adams was inaugurated in 1797. He wrote his wife, “I was very unwell, had no sleep the night before, and really did not know but I should have fainted in the presence of all the world.” Adams promised to retain Washington’s cabinet and continue his policies, but the Hamiltonians felt he was too lenient toward the increasingly hostile Jeffersonians. Soon Adams was characteristically at odds with everyone. “All the Federalists seem to be afraid to approve anybody but Washington,” he noted.

At this time, the French were in the throes of an excessively bloody revolution, which horrified President Adams. He saw it as totally different from the American Revolution. Never having made friends with the pro-French faction, and believing government should be “a government of laws and not of men,” he tried his utmost to prevent America from joining England in a war against France. Adams announced a war crisis, and recommended the arming of merchant vessels, the enlargement of the navy, and reorganization of the militia. This request was dwindled down by Congress to the authorizing of three frigates and the calling out, if needed, 80,000 militiamen.

Adams also sent commissioners to France. Word reached the United States that the French Directory refused to negotiate with the commissioners, unless they would first pay a large bribe of $250,000 (today around $8,100,000), and offer an apology for Adams’s criticism of France. The names of the Frenchmen imposing these conditions were Hottinguer, Bellamy, and Hauteval, much better remembered as “X, Y, and Z.” Said now popular President Adams, “I will never send another minister to France without assurances that he will be received, respected, and honored as the representative of a great, free, powerful, and independent nation.”

But one thing that contributed to the downfall of the popularity of the Federalists was the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. Though Adams did not originate the Acts, he did sign them into law. Their enforcement resulted in the prosecution and conviction of several Jeffersonian editors. One of the first to be sent to jail was Congressman Matthew Lyons of Vermont. He freely and openly criticized Adams until the issue exploded in the House chamber, where Lyons and another Congressman attacked each other with fire tongs and a stick. Lyons was labeled in the newspapers as “First martyr under federal law the junto dared to try on.” Obviously, the intention of the Acts was to clear the country of foreign agents, and silence anyone who published “false, scandalous, and malicious writings” against the President, meaning Jeffersonian editors. The law was deemed an abuse of power and unconstitutional by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who organized the first states’ rights movement.

“A peck of troubles in a large bundle of papers, often in a handwriting almost illegible, comes every day. . . there is no pleasure,” Adams grumbled about the presidency. Besides being distrusted, he was attacked for spending summers at his farm. But “the volume of business was so slight,” records a history of the presidency, “that Adams could conduct it from a single stand-up desk in which he allotted a pigeonhole to each department.” Another problem worth grumbling about was the extensive entertaining expected, coming out of the President’s own salary. For one Fourth of July reception for Congress, Adams personally paid for two-hundred pounds of cake.

Saving the nation from a needless war with France Adams considered his crowning achievement. President Adams also appointed his son John Quincy as minister plenipotentiary to Prussia. In 1798, he signed an act establishing the Mississippi Territory. He never exercised the veto. On November 1, 1800, Adams moved into the still unfinished White House. The first letter from the building was one to his wife: “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of blessings on this house and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but wise and honest men ever rule under this roof.”

By the election of 1800 the Jeffersonians were a united group, but the Federalists were horribly divided. Having received eight fewer electoral votes than Jefferson, Adams was not reelected. “He was very sensibly affected,” penned Jefferson, “and accosted me with these words: ‘Well, I understand that you are to beat me in this contest, and I will only say that I will be as faithful a subject as any you will have.’” Nonetheless, Adams left the city the day before the popular Jefferson was sworn in as President.

Adams retired, at age sixty-five, to his farm in Massachusetts, called Peacefield. Several years later, Philadelphia doctor Benjamin Rush encouraged Adams and Jefferson to heal the marred friendship resulting from their political differences. “I have always loved Jefferson, and still love him,” Adams proclaimed. Adams finally wrote Jefferson a few days after Christmas 1811. Jefferson replied, saying he looked forward to another letter about “your health, your habits, occupations, and enjoyments.” He told Adams, “I now salute you with unchanged affection and respect.” Seizing the opportunity, Adams responded, “You and I ought not to die before we have explained ourselves to each other.” They resumed their correspondence.

In later life, Adams remained busy. It is said that he “rejoiced in the size of his manure pile” and “enjoyed his tankard of hard cider before breakfast.” Even in his eighties, Adams consistently took long walks. When his first great-grandchild was born on his eightieth birthday, he said, “Tell her. . .that although life is short, yet it is a very precious blessing, and every moment of it ought to be employed and improved to the best advantage.” He made his last public appearance reviewing U.S. Military Academy cadets. He proudly lived to see his son, John Quincy, become President (though he did not attend the inauguration). Adams died on July 4, 1826, in Quincy. His last words, perhaps spoken with a glimmer of his old humor, were “Thomas Jefferson survives”, unaware that his old rival had died a few hours earlier. It was the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

John Adams once wrote a friend, “If I were to go over my life again, I would be a shoemaker rather than an American statesman.” Though certainly many a fine shoe would have been crafted by Adams, he did well to follow the path of life God showed him.

Assessment

Many, in their assessment of John Adams, suggest he was a vain man. Overshadowed by others in his time (not just physically) by those such as Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and Hamilton whose works were often more highly praised, while Adams remained unpopular, it is understandable he felt slighted. Not to be credited with praise due was hard for him, as one of the hardest working of the founders, to bear. Being human he made mistakes—chief among them the signing of the Alien and Sedition Acts. He was an opinionated man (who, for example, refused to attend the annual celebrations in honor of Washington’s birthday because he considered it deification), but to his credit he was a good discerner of character and “was honest as a politician as well as a man,” said Jefferson. He was also a Christian.

There are many colorful accounts of John Adams’s personality. James Madison recalled that he had “an ardent love of country, and the merit of being a colossal champion of its independence, must be allowed by those most offended by the alloy in his Republicanism, and the fervors and flights originating in his moral temperament.” The best sum of his character is put forth by Jefferson. “He is vain, irritable, and a bad calculator of the force and probable effect of the motives which govern men. This is all the ill which can possibly be said of him. He is as disinterested as the Being who made him. He is profound in his views and accurate in his judgment, except where knowledge of the world is necessary to form a judgment. He is so amiable that I pronounce you will love him, if ever you become acquainted with him.” Franklin got the impression that “I am persuaded. . . that he means well for his country, is always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses.”

A proper closing to the story of a life devoted to liberty are these words spoken by Adams. “I always consider the settlement of America with reverence and wonder, as the opening of a grand scene and design in Providence for the illumination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind ALL OVER THE EARTH.”

Bibliography:

Adams, John, quoted in—Chapman, James A., ed. Handbook of Grammar and Composition, 5th ed. A Beka Book, 2002.

Aikman, Lonnelle. The Living White House. Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 1982.

Allison, Andrew M., Jay A. Parry, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real George Washington, 3rd ed. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Allison, Andrew M., M. Richard Maxfield, K. DeLynn Cook, and W. Cleon Skousen. The Real Thomas Jefferson. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Allison, Andrew M., W. Cleon Skousen, and M. Richard Maxfield. The Real Benjamin Franklin. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2010.

Aronson, Steven M. L. Presidents: Fandex Family Field Guides. New York: Workman Publishing Co., Inc., 2016.

Athearn, Robert G. The American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States, Volume IV: A New Nation. New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1963.

Barton, David, ed. and trans. Wives of the Signers: The Women Behind the Declaration of Independence. WallBuilder Press, 2010.

Caroli, Betty Boyd. First Ladies. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Freidel, Frank. Our Country’s Presidents. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1966.

Hamburger, Kenneth E., Joseph R. Fischer, and Steven C. Gravlin. Why America is Free. Published by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1998.

Lengyel, Cornel Adam. Presidents of the U.S.A.: Profiles and Pictures. Bantam Books, 1961.

Lorant, Stefan. The Presidency. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1952.

Lowman, Michael R. United States History: Heritage of Freedom, in Christian Perspective, 3rd ed. A Beka Book, 2015.

Mattern, David B., ed. James Madison’s “Advice to My Country.” University Press of Virginia, 1997.

Skousen, W. Cleon. The Making of America, 3rd ed., revised. National Center for Constitutional Studies, 2007.

Taylor, Tim. The Book of Presidents. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1989 ed. S. v. “John Adams” by Robert A. East.

[TAGS- John Adams, Revolutionary War, Presidents, leaders, patriots, Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, freedom, Alien and Sedition Acts]