First rising to the spotlight as a model, actress, and television host, Jenny McCarthy faced backlash for her autism awareness advocacy.

Twenty years have passed since Jenny McCarthy became a household name as the original “anti-vaxxer”—a label she has always rejected.

Her journey from an actress to a figurehead of autism advocacy began when her 2½-year-old son was diagnosed with the condition after receiving the MMR vaccine. At the time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) stated position was unequivocal: The vaccine did not cause autism.

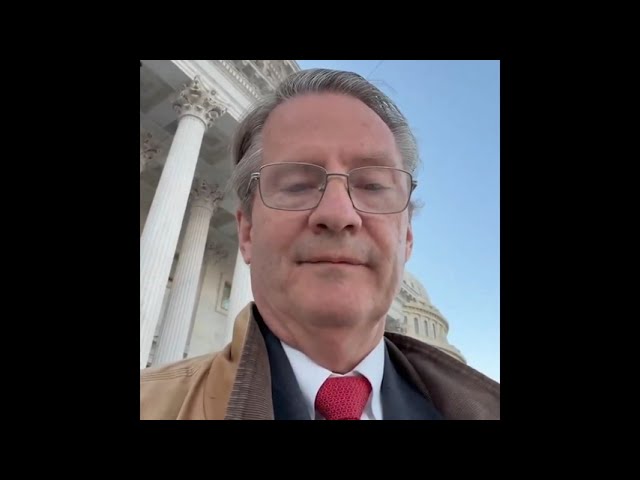

Fast forward to November 2025 and discussion about autism is mainstream; propelled by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s pledge to determine the cause of the condition, which now impacts 1 in 31 children in the United States, according to the CDC.

The CDC has also dropped the definitive position that vaccines do not cause autism—a shift in position that many medics disagree with.

For McCarthy, it is a moment of vindication and of answered prayers.

“A lot still needs to happen,” she told The Epoch Times. “But at least we’re on a path now where children can have a better chance of not having this happen to them, and generations can be saved from the pain that we have gone through as parents.”

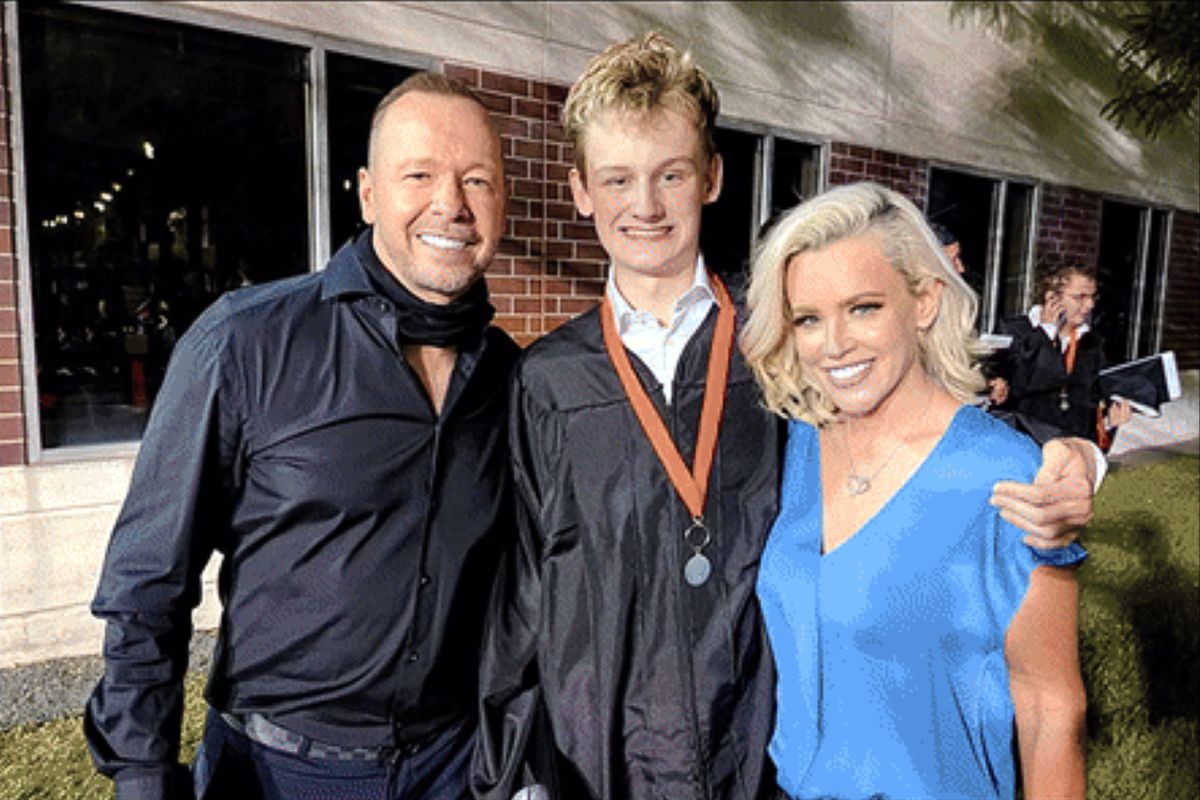

McCarthy, 53, rose to the spotlight as a model, actress, and television host in the 1990s, but became a household name in 2005 after she shared the story of her son Evan’s autism diagnosis.

Along with campaigning for autism awareness, McCarthy did not shy away from her belief that the MMR vaccine had been part of the cause, quickly earning her the anti-vaxxer label.

“As far as I know, I was the first public figure to have that label, even though I have always said I’m not against vaccines, but I’m for vaccine safety,” she said.

From Entertainer to Campaigner

McCarthy’s unexpected path from entertainer to campaigner began a few days before Evan’s MMR shot, when she read a Time magazine feature about parents who said their children developed symptoms of autism after receiving the vaccine.

“I felt a pit in my stomach, perhaps mother’s intuition, that Evan should not get this shot,” McCarthy said. Then, McCarthy was married to film director John Asher, who was also at the appointment.

McCarthy expressed her concerns to the pediatrician and referenced the article. She asked if he could hold off on the vaccine.

“He got very angry at me and said it was just parents’ desperate attempts to blame something. He said the vaccine had nothing to do with it,” McCarthy said.

She refused to sign a waiver allowing the physician to administer the MMR vaccine. Asher signed it, and Evan received the shot.

That is when life for son and mother abruptly changed.

“Until that point, he had hit every milestone that a child his age should reach. After the MMR shot, he started showing regression. His babbling stopped. Eye contact went away. He no longer smiled,” McCarthy said.

“He developed blue circles under his eyes, a bloated belly, gas, constipation, eczema, yeast,” she added. “I didn’t know then that these are all comorbid conditions that go with autism. I didn’t know why Evan was suddenly unhealthy and sick.”

McCarthy does not believe that the MMR shot alone triggered Evan’s autism. She blames “a compilation of so many shots to a kid who clearly had autoimmune disorders.”

Still, Evan’s most serious reaction occurred after the MMR vaccine.