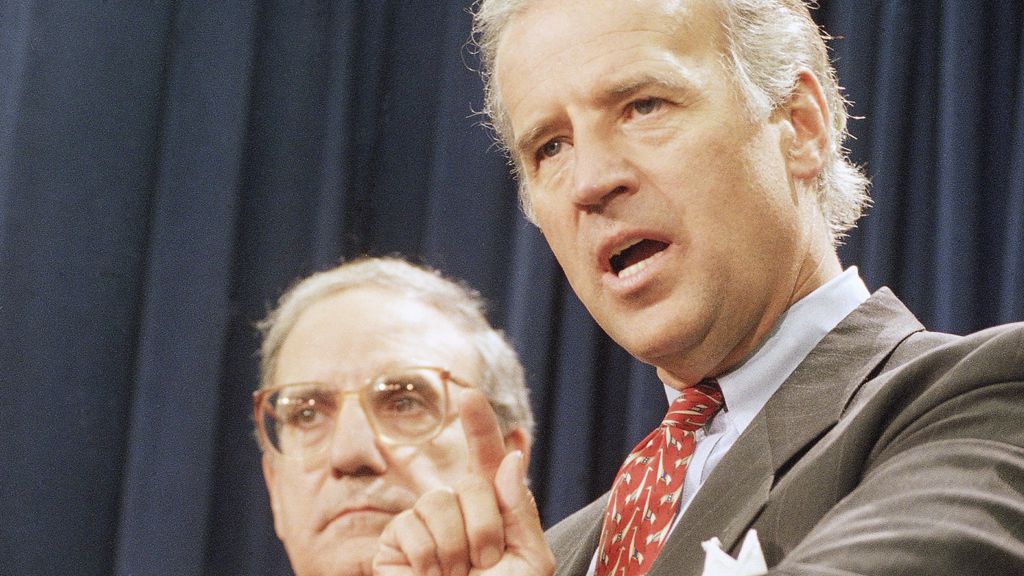

WASHINGTON — In September 1994, as President Bill Clinton signed the new Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act in an elaborately choreographed ceremony on the south lawn of the White House, Joseph R. Biden Jr. sat directly behind the president’s lectern, flashing his trademark grin.

For Mr. Clinton, the law was an immediate follow-through on his campaign promise to focus more federal attention on crime prevention. But for Mr. Biden, the moment was the culmination of his decades-long effort to more closely marry the Democratic Party and law enforcement, and to transform the country’s criminal justice system in the process. He had won.

“The truth is,” Mr. Biden had boasted a year earlier in a speech on the Senate floor, “every major crime bill since 1976 that’s come out of this Congress, every minor crime bill, has had the name of the Democratic senator from the State of Delaware: Joe Biden.”

Partial Transcript

0:00/0:53

We must take back the streets. It doesn’t matter whether or not the person that is accosting your son or daughter, or my son or daughter, my wife, your husband, my mother, your parents — it doesn’t matter whether or not they were deprived as a youth. It doesn’t matter or not — whether or not they had no background that enabled them to have — to become social — become socialized into the fabric of society. It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re the victims of society. The end result is, they’re about to knock my mother on the head with a lead pipe, shoot my sister, beat up my wife, take on my sons. So, I don’t want to ask, “What made them do this?” They must be taken off the street. That’s number one.

Now, more than 25 years later, as Mr. Biden makes his third run for the White House in a crowded field of Democrats — many calling for ambitious criminal justice reform — he must answer for his role in legislation that criminal justice experts and his critics say helped lay the groundwork for the mass incarceration that has devastated America’s black communities. That he worked with segregationists to write the bills — an issue that recently dominated the political news and seems likely to resurface in Mr. Biden’s first debate on Thursday — has only added to his challenge. So has the fact that black voters are such a crucial Democratic constituency.

Mr. Biden apologized in January for portions of his anti-crime legislation, but he has largely tried to play down his involvement, saying in April that he “got stuck with” shepherding the bills because he was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. But an examination of his record — based on newly obtained documents and interviews with nearly two dozen longtime Biden contemporaries in Washington and Delaware — indicates that Mr. Biden’s current characterization of his role is in many ways at odds with his own actions and rhetoric.

Listen to ‘The Daily’: Joe Biden’s Record on Race

Hosted by Michael Barbaro, produced by Alexandra Leigh Young and Eric Krupke, with help from Jessica Cheung and Luke Vander Ploeg, and edited by Lisa Tobin and Marc Georges

As a senator, he opposed busing and championed laws that transformed the criminal justice system. Now, as a presidential candidate, he faces renewed scrutiny over the legacy of those decisions.

Transcript

0:00/31:28

Michael Barbaro

From The New York Times, I’m Michael Barbaro. This is “The Daily.”

Today: In the Democratic race for president, Joe Biden is being asked to confront a record on race that some in his party now see as outdated and unjust. Astead Herndon on the policies Biden embraced and how they were viewed when he embraced them.

It’s Wednesday, July 3.

Archived Recording (Kamala Harris)

I do not believe you are a racist. And I agree with you when you commit yourself to the importance of finding common ground. But I also believe — and it’s personal. And I was actually very — it was hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country. And it was not only that, but you also worked with them to oppose busing. And there was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools. And she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me. So I will tell you that on this subject, it cannot be an intellectual debate among Democrats. We have to take it seriously. We have to act swiftly.

Michael Barbaro

Astead, to the average American watching the debates last week, what do you think that this now famous confrontation between Joe Biden and Kamala Harris seemed to be about?

Astead Herndon

On its most literal level, it was two top-tier Democrats having the most confrontational, direct moment we’ve seen in the primary so far.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

If we want to have this campaign litigated on who supports civil rights and whether I did or not, I’m happy to do that. I was a public defender. I didn’t become a prosecutor. I came out, and I left a good law firm to become a public defender, when, in fact — [APPLAUSE] — when, in fact, my city was in flames because of the assassination of Dr. King.

Astead Herndon

But in the bigger, more abstract view, these were two different generations of Democrats. One, a barrier-breaking, younger black senator, pushing the old guard, the senator who came in the 1970s, who had relationships with segregationists and avowed racists. She was pushing him on racial issues and trying to hold him accountable for how the Democratic Party has handled issues of race for decades leading up to this point.

Michael Barbaro

But it also felt like this was about the details of a specific policy that Biden was a part of. And most of us probably don’t really understand what his intentions were or what the context of that policy was. So take us back to that time. Where was Joe Biden in his political career?

Astead Herndon

Well, Joe Biden began as a lawyer in Wilmington and, eventually, a city councilor in the county. And he was emerging at a really racially contentious time within the city and state.

Archived Recording

In April, after the murder of Martin Luther King, the National Guard was called out in several cities to put down riots. One of these cities was Wilmington, Delaware. But now, in Wilmington, the National Guard is still on duty. And the governor, Charles Terry, has no plan to send it back.

Astead Herndon

And Joe Biden runs for Senate in 1971 as a new type of Democrat —

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

I’m Joe Biden, and I’m a candidate for the United States Senate.

Astead Herndon

— a Democrat who understands black communities and has personal and deep relationships in those communities, but as a Democrat who can also unite the kind of outer portions of the state, which saw those issues very differently.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

Politicians have done such a job on the people that the people don’t believe them anymore. And I’d like a shot at changing that.

Astead Herndon

Joe Biden himself tells a story about how he was the only lifeguard at a newly integrated pool in Wilmington.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

I applied to the city of Wilmington for a job, and I was the only white employee here. And I learned so much. And I realized that I live in a neighborhood where I could turn on the television, and I’d see and listen to Dr. King and others. But I didn’t know any black people. No, I really didn’t. You didn’t know any white people either. That’s the truth.

Astead Herndon

It was part of his identity and part of his brand that he cared about civil rights, understood the plight of African-Americans in Wilmington, but also, he understood that kind of outer white Delaware was really motivated around grievance at the time. In 1971, a group of black students had filed a lawsuit in hopes to get the schools to further desegregate. And so the question of school segregation and school integration was very much on the forefront of the state’s politics. And at the exact same time, that’s when the young Joe Biden makes his way to Capitol Hill.

Michael Barbaro

And what was Biden’s position when it came to desegregation?

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

Where the court has concluded that a school district, a state, or a particular area has intentionally attempted to prevent black, or any group of people, from attending a school, the court should and must declare that to be unconstitutional and thereby move from there to impose a remedy to correct the situation.

Astead Herndon

Joe Biden takes the position, as many other politicians did at that time, that they were not opposed to the idea of integration. What they’re opposed to was the remedy.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

I have argued that the least effective remedy to be imposed is the busing remedy.

Astead Herndon

You get a court order in the late ‘70s that says that Delaware schools are too racially segregated, and they must form a plan for racial integration. And a plan is instituted by the courts that says, from the city in Wilmington, which is majority black, and the suburbs outside of it, that both those groups of students were for some portion of their schooling going to have to bus to the opposite community. So for the kind of inner city students, which are majority black, they were going to have to go out to the suburbs for six years. And the outer suburbs would have to come into Wilmington schools for about three years. So this becomes the plan that’s put in place that inflames those racial tensions on both sides of the state.

Michael Barbaro

And what is Biden’s opposition to that specific solution?

Astead Herndon

That the idea of integration was not a problem, but it was how the courts were forcing them to go about it. You have to think — if you were a parent in the suburbs, which is almost exclusively white, who had made that choice for your family almost entirely around the school district that your child was supposed to go into. And then there is a court order that comes down that says not only are different people coming to that school, but that your child is going to be put on a bus to a different school. That is the logic that those parents used to oppose the idea of busing. And so at one point in 1975, Joe Biden says, the real problem with busing is you take people who aren’t racist, people who are good citizens, who believe in equal education and opportunity, and you stunt their children’s intellectual growth by busing them to an inferior school. And you’re going to fill them with hatred.

Michael Barbaro

So Biden is sympathizing with white parents in the suburbs who are suddenly feeling dislocated by this decision. But what about black parents in this city whose children would be bused to these theoretically better schools in the suburbs? What is Biden saying to them?

Astead Herndon

This is an important point. Although the kind of white suburbs were almost uniformly against busing, somewhat because of the method and sometimes because of pure racism, in black communities, particularly in Wilmington, there is not universal agreement on this issue. There is universal consensus that integration is important and that their schools had not been adequately funded or not been adequately supported by the state. But when you look at polling and when you talk to people at the time, the actual issue of busing is controversial. Remember, these parents themselves had to send their children further away into neighborhoods and communities that may have not always been welcoming to those students. So it wasn’t universally loved. In one poll, about 40 percent of black parents supported the idea, 40 percent were against it, around 20% were unsure. Joe Biden tries to take a nuanced position, where sometimes it seems like he is a vocal opponent of the idea of busing and that he is signaling to the kind of white Delaware that he is their advocate.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

And on the issue that the argument is about — and that is whether or not busing is, A, required constitutionally, and B, has a utilitarian value for desegregation — I come down on the side of A, it is not constitutionally required, and B, it is not a useful tool.

Astead Herndon

But there’s other times when he sounds very much like many of the black leaders in Wilmington who say, I don’t know if I like this remedy, but I do know that the issue of integration is really important. So he’s kind of firmly in the middle. And that kind of middle ground is something we see him stake on a number of issues, most notably crime, where he takes the kind of position and relies on those personal relationships with black communities, while, according to his critics, legislating in the interest of white ones.

[Music]

Michael Barbaro

We’ll be right back. So Joe Biden takes the middle ground, or the middle ground for that time, on busing. How do we then see that in his approach to crime?

Astead Herndon

This one’s a little different, because while Biden on busing was seen as kind of emblematic of the larger Democratic stance, with crime, he was really kind of pushing the boundaries. At that time, particularly in the ‘80s and ‘90s, was a kind of moral panic happening throughout the country —

Archived Recording

Crack, the most addictive form of cocaine, is now sweeping New York.

Astead Herndon

— around the explosion of drugs in cities —

Archived Recording

It’s going nationwide, especially among the young, a drug so pure and so strong, it might just as well be called crack of doom.

Astead Herndon

— and the violent crime that often associated and came with them.

Archived Recording

It’s the devil — see, this cocaine ain’t nothing but the devil, and the devil was telling me to do it.

Astead Herndon

And Biden, as someone who had come up in Wilmington, a community that was experiencing these things closely, he had black community leaders, neighbors of his, saying the issue was very important, but that they were looking at kind of root cause problems of why crime was happening. They were talking about issues like education or job opportunities and the like. When the outer Wilmington and the kind of all-white suburbs, you were hearing a more vocal cry for increasing cops, increasing prisons, and really cracking down on those tough-on-crime measures that came to the cities. So again, Biden is caught between political problem, but also one that’s divided pretty clearly on racial lines.

Michael Barbaro

And so what does he do?

Archived Recording

The truth is every major crime bill since 1976 that’s come out of this Congress has had the name of the Democratic senator from the state of Delaware, Joe Biden, on that bill.

Astead Herndon

There’s this split screen of Joe Biden that you often hear about when you talk to people in Wilmington. There is the neighbor who would go to black churches, would know the kind of leaders by name, and the issues they were advocating for. But then in Washington, you have a Joe Biden that is using those stories of Wilmington to kind of pass more tough-on-crime measures that some in that community say they weren’t asking for. In 1977, he first proposes mandatory minimums for drug sentences. And through the ‘80s, in his connection with Strom Thurmond, they end up passing a really kind of significant set of bills.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

Not enough prosecutors to convict them, not enough judges to sentence them, and not enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.

Astead Herndon

In 1984, that establishes mandatory minimums. In ‘86, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act creates harsher sentences for crack than powder cocaine. And it kind of builds up into the early ‘90s, when Bill Clinton is elected president, the ‘94 bill —

Archived Recording (Bill Clinton)

Thank you, Mr. Vice President, for your introduction and for your labors on this bill.

Astead Herndon

— the “three strikes and you’re out” kind of policy —

Archived Recording (Bill Clinton)

“Three strikes and you’re out” will be the law of the land.

Astead Herndon

— where, if you had three instances of drug offenses or violent drug offenses, it would be an instant life sentence.

Archived Recording (Bill Clinton)

We have the tools now. Let us get about the business of using them.

Michael Barbaro

And what do we understand about how the black community back in Delaware felt about these tough crime measures at the time?

Astead Herndon

Joe Biden talks about, to this day, in his presidential campaign, they make a big point to say that the Congressional Black Caucus overwhelmingly voted for the bill and that black leaders at the time were very supportive of the bill. That is partly true. The Congressional Black Caucus certainly backed the bill after showing some initial wariness. The majority of its members voted for it. There were some vocal black mayors who were calling for these particular measures. But there were also some who were against it.

Archived Recording (Jesse Jackson)

This ill-conceived bill, fed by a media frenzy over crime, was on the fast track to the president’s desk for signature by Christmas.

Astead Herndon

Jesse Jackson spoke out against it.

Archived Recording (Jesse Jackson)

Spending several billion dollars on prisons and longer sentences is not the answer to reducing crime.

Astead Herndon

The head of the Congressional Black Caucus spoke out against it. Representatives like Bobby Scott said they knew that the kind of increase of police in these neighborhoods would cause detrimental effects.

Michael Barbaro

Right. So what turns out to be, over time, the actual impact of all of these bills, including the biggest of them all, that 1994 crime bill, in the years that followed?

Astead Herndon

The undeniable impact is an explosion of America’s prison population that has disproportionately affected black and brown communities. So coming out of the ‘80s and ‘90s, you have a pretty clear articulation from then-Senator Biden that cops and the expansion of cops is a preventative measure.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

In a nutshell, the president’s plan doesn’t include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs.

Astead Herndon

He felt that the kind of presence of police officers, the increased presence of police officers in these communities, would inherently mean that crime would go down. As the years have gone on, it has become clear that the actual effect was not that, but was the disruption of the communities themselves. When I was in Wilmington talking to folks there, they were saying by 1994, it was already clear that the tough-on-crime kind of measures of the ‘80s weren’t working on the streets. It was not decreasing crime, but more importantly, it was causing a kind of incarceration effect that didn’t have the terminology for mass incarceration that we now call it, but it was clear that communities were getting ruptured by the increase in sentences and the increased focus on tough-on-crime measures.

Michael Barbaro

And of course, the legacy of busing is that we’ve seen a resegregation of the U.S. school system, because the job was never really done.

Astead Herndon

Exactly. There is a narrative that busing failed, but the truth is kind of murkier. Busing, as a policy, often did achieve its goals and racially integrate the places it was instituted. What failed was the political will to keep those measures in place that made integration happen and to see racial integration of schools as a necessary problem to solve. So in the last decades, you have not only overturned to pre-busing segregation levels, but in some places, you have racial segregation in schools becoming even worse than they were, or just as bad as they were, at the time of Brown v. Board of Education.

Michael Barbaro

So Astead, it seems like what we’re seeing in the debate last week, in this exchange between Harris and Biden, was that Biden is going to have to confront these past policies as their legacies are understood in the current moment. And that means complicated legacies with real implications, many of them quite negative for the black community.

Astead Herndon

Joe Biden is being — his whole record is being examined in new ways. He’s run for president twice before, but never as a front-runner and never as someone who enjoys this amount of support among black communities. Remember, this is still the vice president to the first black president. This is still the person who is seen, oftentimes, as the most likely to beat President Trump in the Democratic Party, which black communities have often seen as their number one goal. So he’s enjoying this kind of support, robust support, among black communities, while at the same time, his rivals are trying to use his record, particularly on busing and crime, to wrest away those votes. And I think that’s a really interesting question, is will these moments, like the one Senator Harris made happen in the debate, will they start to chip away at that image of him as a champion and an advocate for black communities? As people come to understand the record and as people come to understand the context of Delaware at the time, will he be seen as someone who was navigating a difficult racial terrain or as someone who kept black people close, but fundamentally legislated in the interests of white communities?

Michael Barbaro

And so the question is, will voters evaluate him for what he was trying to accomplish in the ‘70s, and the ‘80s, and the ‘90s, or for what we now understand the impact of those bills to have been up through today? I wonder if you have any sense of how black voters are seeing that from your reporting.

Astead Herndon

I spent a lot of time in South Carolina, where we have the biggest population of black voters in the early states. And Joe Biden enjoys a large amount of goodwill in those places. What that is not is a deep connection to Joe Biden as an individual. As I heard someone say recently, his support is wide, but it’s thin. I think that people vote on a lot of different levels. Voting based on policy and record is one of them. Voting based on emotion, and feeling, and connection is another. And I think in this era for Democrats, and particularly for black Democrats who feel as if Trump has brought in a new era of white identity politics, there’s voting based on fear. And what you hear in South Carolina is not that they want to vote for Joe Biden because they believe in the things that he has done. But they see him as kind of an emergency fix to a much worse problem for them, which they believe is the presidency of Donald Trump.

Michael Barbaro

Astead, is what you’re saying the black voters may be more inclined to go with a safe choice, because in their mind, in this racial climate and in this political climate, the alternative, which is not winning the presidency, is far more threatening than a Democratic candidate with a debatable historical record on race?

Astead Herndon

Yep. And I think it’s important to make distinctions when we talk about black voters. We particularly see that kind of calculation among older black voters and black voters who are in the South. Now among younger voters, we see a bigger willingness to reject Joe Biden because of some of those records and to embrace candidates who are talking more explicitly and openly about structural changes to create racial equity. But among the older voters, who remain the real heart and soul of the black vote and a sizable portion of the Democratic electorate, it’s that calculation of safety that’s really helping Joe Biden right now. But we should also say that among those older voters, many of them can remember 1994 and remember the 1980s and may have themselves supported these bills and seen their thinking change as well. And I think that’s the important thing to not forget, is just as Joe Biden has evolved, so have many of these people. And I’ve talked to people who don’t see what he did as particularly invalidating, frankly, because they have experienced that same evolution. And sometimes, I have talked to people who said that ‘94 crime bill ruined their homes, and they also say they can’t wait to vote for Joe Biden in the primary.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

Before I start, I’d like to say something about the debate we had last night. And I heard, and I listened to, and I respect Senator Harris. But we all know that 30 seconds to 60 seconds on a campaign debate exchange can’t do justice to a lifetime committed to civil rights.

Michael Barbaro

Well, so Astead, what do you make of how defensive Biden has been to these criticisms and these questions about his legacy, rather than acknowledging, a lot has changed since then. I was doing what I thought was best in the moment. I now see, I now understand that it played out differently than I expected.

Astead Herndon

This is a question I’ve thought a lot about. If by the early 1990s, it was clear to the cops on the ground in Wilmington that the tough-on-crime measures didn’t work, that the disparities that were created in the ‘80s between crack and cocaine were disproportionately hurting black communities, why did it take until this year for Joe Biden to acknowledge it himself? And we don’t have clear answers to that.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

I haven’t always been right. I know we haven’t always gotten things right. But I’ve always tried.

Astead Herndon

We know that Joe Biden very rarely apologizes. But it was not until this year that you really have an articulation from Vice President Biden that he played a role as a senator in creating some of these disparities.

Archived Recording (Joe Biden)

That Barack and I finally reduced the disparity in sentencing, which we had been fighting to eliminate, in crack cocaine versus powder cocaine. It was a big mistake when it was made. We thought we were told by the experts that, crack, you never go back. It was somehow fundamentally different. It’s not different. But it’s trapped an entire generation.

Michael Barbaro

Do you think it’s possible that he might fear that if he apologizes, that that might weaken him more with moderate voters who don’t feel that Americans should have to apologize for that period, for those instincts, and for those policies?

Astead Herndon

I think that’s a big possibility. I also think Joe Biden was acting in what he believes was good faith, even at that moment, and what he thinks was the evidence in front of him and the context of the time. I think it’s important to always go back to Delaware with him. And in the moment that he comes up in, it is part of his personal and political identity that he was an advocate for the black communities and that he was performing a new role and, frankly, public service to those communities that white politicians had not done in that state. And so I think it’s bigger than just the political realities of right now and what apologizing would mean. To apologize would go to the heart of what his identity has been since he got in public office in the 1970s.

Michael Barbaro

Mm-hmm. And he’s just not willing to apologize for that. Because in fact, he’s still proud of it.

Astead Herndon

The evidence in front of us tells us that’s true. He was praising the crime bill just years ago. And he has called it, at some points, his greatest accomplishment. And he has shown a real resistance to the many opportunities that activists and other rivals have given him to say that those actions were a mistake.

[Music]

Michael Barbaro

Astead, thank you very much. We appreciate it.

Astead Herndon

Thanks for having me.

Michael Barbaro

We’ll be right back.

Here’s what else you need to know today. On Tuesday, the Trump administration said it would end its attempts to ask about citizenship on the 2020 census, dropping the proposed question from the survey. The decision comes just days after the Supreme Court ruled that the administration had failed to offer a compelling explanation for including the question, which critics said was an attempt to discourage undocumented immigrants from filling out the census, and ultimately, skew the results of the census in favor of Republicans. And House Democrats have filed a lawsuit against the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service, demanding access to President Trump’s tax returns. The lawsuit moves a months-old political dispute between Congress and the White House into the federal courts. At the heart of the fight is whether Congress has the legal right to review the president’s personal financial information. The White House says that such requests must be limited to materials needed to draft laws. House Democrats say that their powers are far broader and are not subject to second-guessing by the executive branch.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m Michael Barbaro. See you on Friday, after the holiday.

Mr. Biden arrived in the Senate in 1973 having forged close ties with black constituents but also with law enforcement, and bearing the grievances of the largely white electorate in Delaware. He courted one Southern segregationist senator, James O. Eastland of Mississippi, who helped him land spots on the committee and subcommittees dealing with criminal justice and prisons, and became a close friend and legislative partner of another, Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

While Mr. Biden has said in recent days that he and Mr. Eastland “didn’t agree on much of anything,” it is clear that on a number of important criminal justice issues, they did. As early as 1977, Mr. Biden, with Mr. Eastland’s support, pushed for mandatory minimum sentences that would limit judges’ discretion in sentencing. But perhaps even more consequential was Mr. Biden’s relationship with Mr. Thurmond, his Republican counterpart on the judiciary panel, who became his co-author on a string of bills that effectively rewrote the nation’s criminal justice laws with an eye toward putting more criminals behind bar

In 1989, with the violent crime rate continuing to rise as it had since the 1970s, Mr. Biden lamented that the Republican president, George H. W. Bush, was not doing enough to put “violent thugs” in prison. In 1993, he warned of “predators on our streets.” And in a 1994 Senate floor speech, he likened himself to another Republican president: “Every time Richard Nixon, when he was running in 1972, would say, ‘Law and order,’ the Democratic match or response was, ‘Law and order with justice’ — whatever that meant. And I would say, ‘Lock the S.O.B.s up.’”

Video

TRANSCRIPT

0:00/0:42

I know it’s hard to believe, but this very day, violent drug offenders will commit more than 100,000 crimes — on this day alone. And the sad part is that we have — we have no more police in the streets of our major cities than we had 10 years ago. And what the president proposes won’t help much. What he proposes is no increase over what the Congress has already approved last year. In a nutshell, the president’s plan doesn’t include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, not enough prosecutors to convict them, not enough judges to sentence them and not enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.

At a time when Democrats tended to espouse the “root cause” theory of crime — the idea that poverty and other social ills bred criminal activity — and Republicans thought punishment was the answer, Mr. Biden wanted to “abandon the old debate,” as he told The Philadelphia Inquirer in June 1994. But he often seemed to tilt strongly toward the Republican view.

“It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re the victims of society,” Mr. Biden said in 1993, adding, “I don’t want to ask, ‘What made them do this?’ They must be taken off the street.”

Mr. Biden declined an interview for this article. In a statement, his campaign said that he had “fought to defeat systemic racism and unacceptable racial disparities for his entire career,” and that he “believes that too many people of color are in jail in this country.” The statement went on, “As president, he would fight to put an end to mandatory minimums, private prisons and cash bail, and he would support automatic expungement for marijuana offenses because he believes no one should be in jail for marijuana.”

On the campaign trail in South Carolina on Saturday, Mr. Biden hinted that he intended to propose a criminal justice reform package to do just that, and also proposed extending Pell education grants to prisoners — moves that would directly repudiate provisions of the 1994 crime bill

“Instead of teaching people how to be better criminals in prison, we should be educating people in prison,” Mr. Biden told the South Carolina Democratic convention.

Biden supporters say his evolution should be admired, that he has grown on criminal justice issues as new evidence has emerged. Citing the strong public support for the crime bill at the time, they said Mr. Biden was responding to a national emergency of drug abuse and violence that had particularly terrorized black communities.

But other Democrats say a fuller reckoning is required.

Representative Bobby Rush, a veteran congressman from Chicago, described the crime bill as “a proverbial Trojan horse” for black communities and called his “yes” vote the worst he had given in more than a quarter-century in the House.

“Did he not know that the war on drugs combined with the legislative imprimatur of the U.S. Congress and federal law would create havoc in our communities?” Mr. Rush said, referring to Mr. Biden. “And I wonder, what was he responding to?”

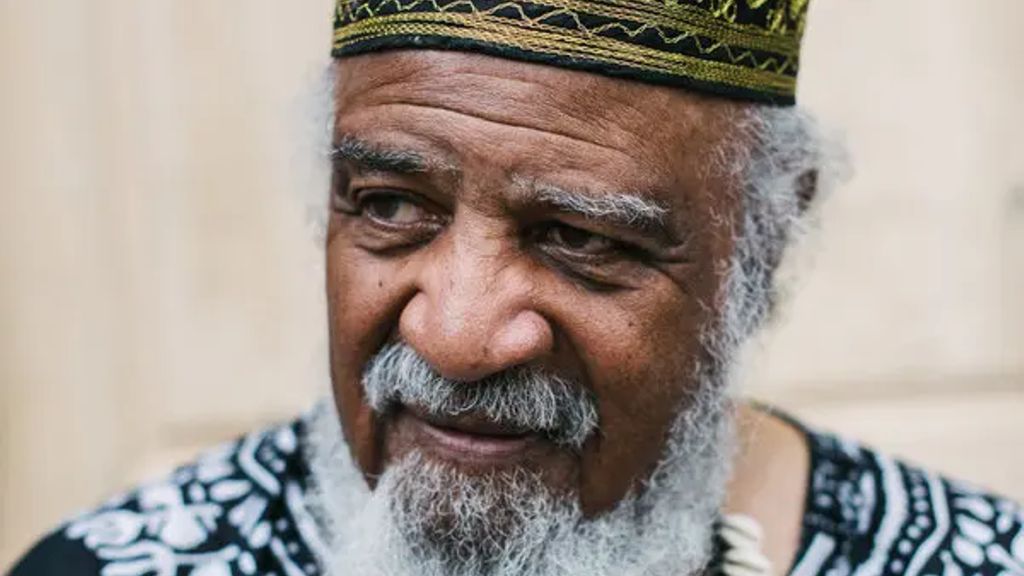

What he was responding to, according to Harmon Carey, director of the Afro-American Historical Society in Wilmington, were the powerful political currents of his home state. During the 1980s and 1990s, Delaware was a place in transition, with a booming financial-services culture clashing with the rising poverty, crime and racial tension in Wilmington, the state’s largest city, which is also majority-black.

“Joe’s a decent fella, but he was doing what his white constituents wanted,” Mr. Carey said. “The white people wanted to send people to prison. They wanted cops. And that’s what he did.”

Racial Ferment in Delaware

Mr. Biden was a political unknown, a onetime public defender who had served just two years on the New Castle County Council, when he pulled off a stunning electoral upset, unseating a popular Republican senator by a margin of less than 1 percent. The year was 1972. The new senator-elect was 29.

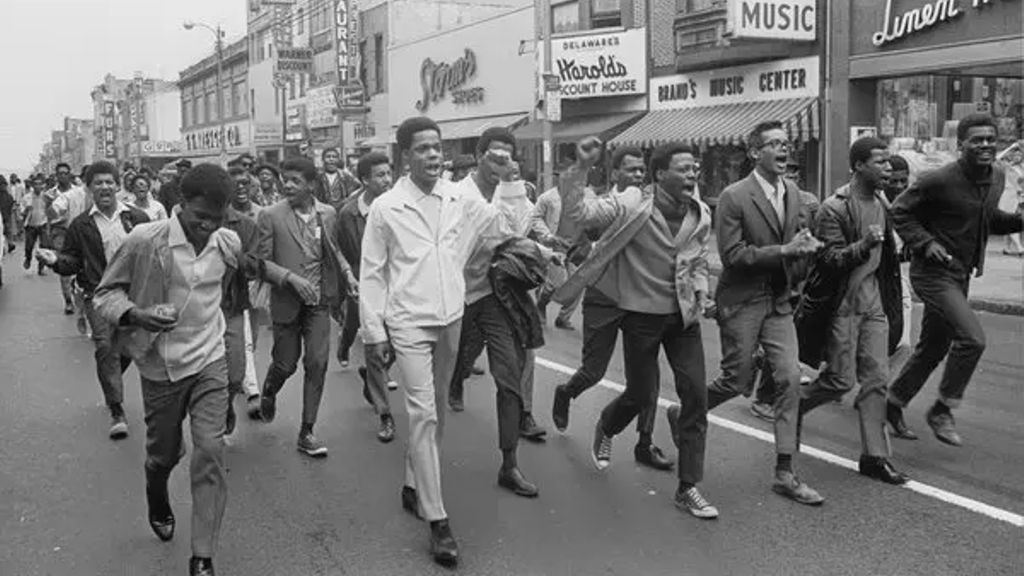

Marching in Wilmington in the aftermath of the 1968 rioting and National Guard occupation.

He had come of age during a time of intense racial ferment in his adopted state. Wilmington erupted in rioting after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in the spring of 1968, and the governor imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew and called in the National Guard, an occupation that lasted nine months. In 1971, black students in the city filed a class-action lawsuit to force schools to desegregate.

In this environment, Mr. Biden would quickly position himself as a new type of white politician: always approachable, with meaningful personal relationships in black communities. To this day, Mr. Biden tells the story of how, home from college for the summer, he was the only white lifeguard at a largely black municipal swimming pool.

“The nightly news had a way of making these stories seem like a conversation between the races in Wilmington, but I knew blacks and whites weren’t talking to one another,” Mr. Biden wrote in his autobiography “Promises to Keep.” “I knew that from my experience at [the] swimming pool.”

The Wilmington swimming pool where Mr. Biden once worked as a lifeguard has been renamed in his honor.

Still, his relationship with Wilmington’s black community was complicated. As a freshman senator, he spoke out against the state’s court-ordered school-busing program. Busing was not universally popular among African-Americans, several community leaders recalled in interviews, but Mr. Biden’s vocal opposition went further.“The real problem with busing,” Mr. Biden said in 1975, “is you take people who aren’t racist, people who are good citizens, who believe in equal education and opportunity, and you stunt their children’s intellectual growth by busing them to an inferior school, and you’re going to fill them with hatred

From his first term, Mr. Biden made his focus clear: the environment, a balanced budget and, especially, crime — all issues that other Democrats were not addressing, said Ted Kaufman, one of Mr. Biden’s closest and longest-running advisers.

“He knew and said that the main victims of crime were in the African-American community, so he ran on saying we have to do something about getting tough on crime,” Mr. Kaufman said, adding that Mr. Biden had also stressed the need to protect defendants’ civil liberties.

That tough-on-crime stance, Mr. Kaufman said, was “a very popular position to take in the African-American community.” But in interviews with community leaders in Wilmington, not everyone agreed. Though they remembered Mr. Biden fondly and said he remained widely popular in the black community, several stressed that their focus had been on systemic problems like economic inequality and failing schools — not on getting more police officers and prisons.

“We thought job opportunities would reduce the number of people on the corners resorting to drugs and crimes,” said the Rev. Dr. Vincent Oliver, a Wilmington pastor and longtime civil-rights activist.

Added James M. Baker, a former Wilmington mayor, who is black, “We knew you couldn’t arrest your way out of the problem.”

But Mr. Biden’s newfound agenda did appeal to a different, and larger, segment of Delaware’s electorate: white voters. In Delaware, the southern portions of the state are often likened to the lands of the Old South; and at the same time, many northern white liberals had fled Wilmington and shared Mr. Biden’s opposition to busing. In 1978, Mr. Biden would cruise to re-election, winning by 17 points

In his next term, Mr. Biden would begin a legislative push against crime that would last nearly two decades. In that time, according to Mr. Carey, the historical society leader, he often struck a careful balance, using personal relationships to maintain his good standing in Delaware’s black community, while carefully legislating in the more conservative interests of white voters and law enforcement.

Harmon Carey, head of the Afro-American Historical Society in Wilmington, said Mr. Biden’s approach to crime legislation reflected “what his white constituents wanted.”

The crime legislation would mark his hometown — and hometowns across America — forever.

Current statistics from the United States Bureau of Prisons show that African-Americans, who make up roughly 12 percent of the American population, account for 37.5 percent of the federal prison population. And an October 1995 report by The Sentencing Project, which advocates criminal justice reform, found that between 1989 and 1995 the percentage of young black men who were either on probation, in prison or jail jumped to 32 percent from 23 percent.

“We got the wrong kind of police. Not the community police, just more police who weren’t sensitive to black and brown people. We got more prisons,” Mr. Oliver said. “I don’t know what drove him to do it, I don’t know the political landscape, but that wasn’t what we were calling for. Not at all.”

Forging Ties With Segregationists

Even before he was sworn into the Senate in January 1973, Mr. Biden wrote Mr. Eastland, the powerful chairman of the Judiciary Committee, expressing his interest in a seat on the panel. A Democrat and wealthy plantation owner from Mississippi, Mr. Eastland was one of the “old bulls” of the Senate, an unabashed Dixiecrat and foe of integration who referred to black people as “an inferior race.”

Senator Strom Thurmond, left, served with Mr. Biden, center, on the Senate Judiciary Committee. Together, they wrote roughly a half-dozen crime bills.

Mr. Biden recently has tried to minimize his alliance with Mr. Eastland, saying he had to “put up with” the senior Democrat. But letters between them, archived at the University of Mississippi and published this year by CNN and The Washington Post, show that Mr. Biden courted the older man, who saw him as a kindred spirit in their opposition to busing and became a mentor to the young senator.

Mr. Biden finally landed a seat on the judiciary panel in February 1977, and wrote to Mr. Eastland again, petitioning to be put in charge of the subcommittee overseeing prisons and sentencing. By year’s end, with Mr. Eastland’s support, he was pushing to narrow judicial discretion by creating a commission to set “presumptive sentences,” and to eliminate pardons and parole. His aim, he told his hometown newspaper, The Wilmington Evening Journal, was “equitable and definitive sentences for all,” including defendants “who don’t meet the middle-class criteria of susceptibility to rehabilitation.”

Image

The segregationist Mississippi senator James Eastland, right, pictured with Edward Kennedy, helped Mr. Biden get committee assignments relating to criminal justice.

The segregationist Mississippi senator James Eastland, right, pictured with Edward Kennedy, helped Mr. Biden get committee assignments relating to criminal justice.Credit…Henry Griffin/Associated Press

In 1981, when Democrats lost the Senate, Republicans installed another old bull Southern segregationist as chairman: Mr. Thurmond, a Democrat-turned-Republican from South Carolina, who had run for president in 1948 on the Dixiecrat platform. Mr. Biden became the ranking Democrat on the committee.

Over the next decade — first with Mr. Thurmond as chairman and then Mr. Biden after Democrats won back the Senate in 1986 — the pair wrote roughly a half-dozen crime bills together, laying the groundwork for three of the most significant pieces of crime legislation of the 20th century: the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, establishing mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses; the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which dictated much harsher sentences for possession of crack than for powder cocaine; and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, a vast catchall tough-on-crime bill that also included money for prevention, including Mr. Biden’s signature initiative, the Violence Against Women Act.

It was not only a partnership, but also a friendship, Mr. Biden recounted in 2003 when he spoke at Mr. Thurmond’s funeral — even as he acknowledged that he had arrived in the Senate “emboldened, angered and outraged” by Mr. Thurmond’s past.

“Strom and I shared a life in the Senate for over 30 years,” Mr. Biden said in his eulogy. “We shared a good life there and it made a difference. I grew to know him. I looked into his heart and I saw a man, the whole man. I tried to understand him. I learned from him and I watched him change, oh so subtly.”

Crack Cocaine and ‘a Tragic Mistake’

In June 1986, a star forward for the University of Maryland basketball team, Len Bias, died of a cocaine overdose, two days after he had signed with the Boston Celtics. His death created a media frenzy amid a national panic over crack, a cheap, smokable form of cocaine that was alarming drug-abuse experts and fueling a wave of violent crime in American cities, especially black neighborhoods.

Mr. Biden convened a hearing the next month. Among the witnesses was Dr. Robert Byck, a Yale psychiatry professor and a leading expert on cocaine. He warned of a crack epidemic in the nation’s cities and pleaded for more money for prevention and research.

Image

After the college basketball star Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose in 1986, lawmakers expanded on Mr. Biden’s 1984 bill that had created mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses.

After the college basketball star Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose in 1986, lawmakers expanded on Mr. Biden’s 1984 bill that had created mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses.Credit…Bill Smith/Associated Press

“How likely is it if someone smokes some crack today that they will be addicted in five weeks from now?” Dr. Byck said. “We don’t know answers to simple questions like that.”

Lawmakers responded by expanding on the 1984 bill that had created mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. The 1986 law set a minimum of five years for 5 grams of crack or 500 grams of powder cocaine, the so-called 100-to-1 sentencing disparity.

A 2002 report to Congress from the United States Sentencing Commission found that in 1992, 91.4 percent of federal crack cocaine offenders were black. In releasing a 2006 report on the 1986 measure, the American Civil Liberties Union called the law “a tragic mistake.”

“There was a belief that crack was more potent,” said Ron LeGrand, a former prosecutor who spent three years at the Drug Enforcement Administration and joined Mr. Biden’s staff in 1987. “It wasn’t based on any science; we just thought it was.”

The bill did include money for prevention, which Mr. Biden lauded as its “most important provisions” when he spoke about it on the Senate floor. But it took more than two decades — until 2007 — for Mr. Biden to call for undoing the crack-powder disparity, which he called “arbitrary, unnecessary and unjust,” while acknowledging his own role in creating it.

“I am part of the problem that I have been trying to solve since then,” he said in 2008, “because I think the disparity is way out of line.”

Three Strikes, You’re Out

In Mr. Clinton’s State of the Union address in 1994, he touted his “three strikes and you’re out” proposal, which would incarcerate certain repeat violent offenders for life, and called on Congress to pass a “strong, smart, tough crime bill.” Mr. Biden took up the call.

Image

For President Bill Clinton, signing the 1994 law was an immediate follow-through on his campaign promise to focus more federal attention on crime prevention.

For President Bill Clinton, signing the 1994 law was an immediate follow-through on his campaign promise to focus more federal attention on crime prevention.Credit…Dennis Cook/Associated Press

“What do you need?” he asked in a Senate floor speech that year — it was, he said, the question he had put to police unions while preparing the bill. “They said, ‘The first thing we need is we need more cops.’ And they said, ‘The second thing we need is we need more prisons.’”

Several police unions did not respond to requests for comment.

Violent crime had hit its peak in 1991, with 758 violent crimes per 100,000 Americans, federal statistics show — more than twice the 1970 rate. By the time the 1994 bill was passed, the crime rate was on the decline.

In other Senate floor speeches in 1993 and 1994, Mr. Biden spoke openly of wanting, as Mr. Clinton did, to rid Democrats of their reputation of being soft on crime. Mr. Biden presented the moment as a political window long overdue.

“One of the things I want to do, in addition to end the crime, is end the political carnage that goes on when we talk about crime,” Mr. Biden said. “This is one of these issues that I hope, after this bill, will be moved out of the gridlock category and into an emerging consensus.”

Yet at the same time, Mr. Biden appeared to be evolving. Aides say that by the mid-1990s he was concerned about possible inequities from the 1986 legislation, and his rhetoric reflects a certain shift.

At a 1993 symposium, he called for undoing some mandatory minimums he had helped create, saying they were “not positive” and were “counterproductive.” The next year, he called the three-strikes provision “wacko.” Mr. Biden became a more vocal advocate of diversion programs for first-time offenders, including boot camps and some drug courts.

“It is not enough simply to keep building prisons,” he said in June 1994, because statistics showed that “the prison population keeps growing to fill new spaces.”

The bill he helped fashion — the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 — reflects those varied interests. It was a vast catchall bill that had a string of punitive measures desired by law enforcement. It banned assault weapons, created 60 new death penalty offenses, stripped federal inmates of the right to obtain educational Pell grants, gave states incentives to build prisons, set aside money for 100,000 new police officers and codified the three-strikes rule.

But it also had prevention programs and other measures intended to woo skeptical Democrats, including the Violence Against Women Act to support female victims of crime; drug courts to offer treatment for first-time offenders; a “safety valve” provision, backed by Mr. Biden, allowing limited waivers from mandatory minimums; and money for a “midnight basketball” program to keep inner-city youth off the streets. That portion drew derision from Republicans, who cast the entire bill as soft on crime and chock-full of Democratic social welfare programs.

Like Mr. Biden’s other crime initiatives, the 1994 bill created a personal conundrum: How could he help lift up and protect his black constituents from crime without decimating their neighborhoods by sending a disproportionate number of black people to prison?

“The criminal justice system has a disparate impact on black people,” said Carol Moseley Braun, a former senator from Illinois who is black and supported the bill. “Was Joe mindful of this? Yes, he was. Did we discuss it? Yes, we did.”

Image

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, pictured with Vice President Al Gore in fall 1994, said that year’s crime bill portended “the most fascist period of our history.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, pictured with Vice President Al Gore in fall 1994, said that year’s crime bill portended “the most fascist period of our history.”Credit…Afro American Newspapers/Gado, via Getty Images

Black leaders, though, were bitterly split over the measure. Baltimore’s mayor, Kurt Schmoke, was in favor, as were black mayors in Atlanta, Cleveland, Detroit and Denver. The Rev. Jesse Jackson was against, calling the bill a harbinger of “the most fascist period of our history.”

In the House, the Congressional Black Caucus, then led by Kweisi Mfume, blocked an early version of the bill because of concerns over its punitive measures. But after money for prevention was added, Mr. Mfume switched his position. Of 40 Congressional Black Caucus members, 25 voted for the bill, 12 voted against and three didn’t vote.

One of those who voted against it, Representative Bobby Scott of Virginia, called the bill a political document rather than one based on evidence of and research into what would actually reduce crime.

“We were told that ‘three strikes and you’re out’ polls better than anything you could blurt out in a campaign, including the environment, Social Security, education,” he said in a recent interview. “That was the evidence and research we used to put in that bill.”

In August 1994, as the measure passed the Senate, Mr. Biden said he was giving his constituents back home exactly what they wanted.

“The telephones in the State of Delaware are ringing off the hook,” he said in a speech on the Senate floor, dismissing Republican complaints of “pork” in the bill. “They are not talking about pork or pork chops or anything else. They are saying: ‘Pass the crime bill. Give me 100,000 cops, build more prisons, and get on with it.’ “

Bobby Cummings, who was a rising star in the Wilmington Police Department in the 1980s and eventually became police chief, said the senator was beloved by hometown police officers because he had helped them get “more resources, more people on the street.”

But by 1994, Mr. Cummings said, it was already clear inside the police department that the cops-first approach was not working on the street.

Image

Bobby Cummings, former police chief in Wilmington, said Mr. Biden’s earliest crime-prevention efforts ingratiated him with the police. But by 1994, he said, it was clear that putting more officers on the street wasn’t the solution.

Bobby Cummings, former police chief in Wilmington, said Mr. Biden’s earliest crime-prevention efforts ingratiated him with the police. But by 1994, he said, it was clear that putting more officers on the street wasn’t the solution.Credit…Hannah Yoon for The New York Times

“It didn’t make people safer,” he said. “Really I don’t think anything changed except it threw people in jail.”

‘You Should Repair Damage Done’

The legacy of the 1994 crime bill is mixed. While some studies show that it did lower crime, there is also evidence that it contributed to the explosion of the prison population. Biden aides and supporters often note that the trend toward mass incarceration began much earlier, in the 1970s, and that states — not the federal government — house an overwhelming majority of the nation’s inmates.

That is true, said Vanita Gupta, who led the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Barack Obama and now runs the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. But the 1994 bill, she said, “created and calcified massive incentives for local jurisdictions to engage in draconian criminal justice practices that had a pretty significant impact in building up the national prison population.”

Image

As many of his Democratic opponents call for ambitious criminal justice reform, Mr. Biden must answer for his role in creating some of the most significant pieces of crime legislation of the 20th century.

As many of his Democratic opponents call for ambitious criminal justice reform, Mr. Biden must answer for his role in creating some of the most significant pieces of crime legislation of the 20th century.Credit…Eric Thayer for The New York Times

But Mr. Kaufman, Mr. Biden’s close adviser, who briefly succeeded him as senator after Mr. Biden became vice president, said that was not the bill’s intent: “We were focused on how to effectively and fairly reduce violent crime. That was the charge given to us by community leaders and voters — including of color.”

Mr. Biden long defended the bill, saying as recently as 2016 that it “restored American cities” and that he was not ashamed of it. Looking ahead, even Biden supporters say it is now up to the former vice president to explain his role — and how he views his own legacy.

“It’s a fair question that people ask among members of the black community about this issue of mass incarceration and disparate impact,” said Gregory M. Sleet, a retired federal judge whom Mr. Biden had helped install as the first black United States Attorney in Delaware. “It’s a fair conversation to have about his role,” he said, adding that he thought Mr. Biden had good intentions and had worked with the best evidence he had at the time.

Mr. Biden, critics of the measure say, needs to explain what he will do next.

“I think that’s his challenge; I’ll be listening and observing,” Mr. Jackson said in an interview. “When you harm somebody, you should atone for a sin; you should repair damage done. That’s how you get redeemed.”

By Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Astead W. Herndon

June 25, 2019