Specific unambiguous answers to academic examination questions, those really important questions that need proper essential solutions, are essentially not as important in the process of education as are the type and form of questions students are called on to answer on classroom tests. School students throughout the USA are ordinarily tasked with learning the various disciplines, such as math, science, English, history, etc. that comprise well-rounded high school and college educations; and to show that they have achieved standard levels of knowledge about these disciplines, they are required to undergo examinations or tests to demonstrate these abilities. Moreover, examinations for knowledge and skill proficiency extend beyond the school classroom to private-sector and government employers to determine who can, and can’t, demonstrate skill competence in doing required job duties. The correct type of examinations administered to students and job candidates should therefore properly determine whether or not students have mastered the required studies that allow them to be passed from grade-level to grade-level and job candidates the skills that they need to be successfully employed.

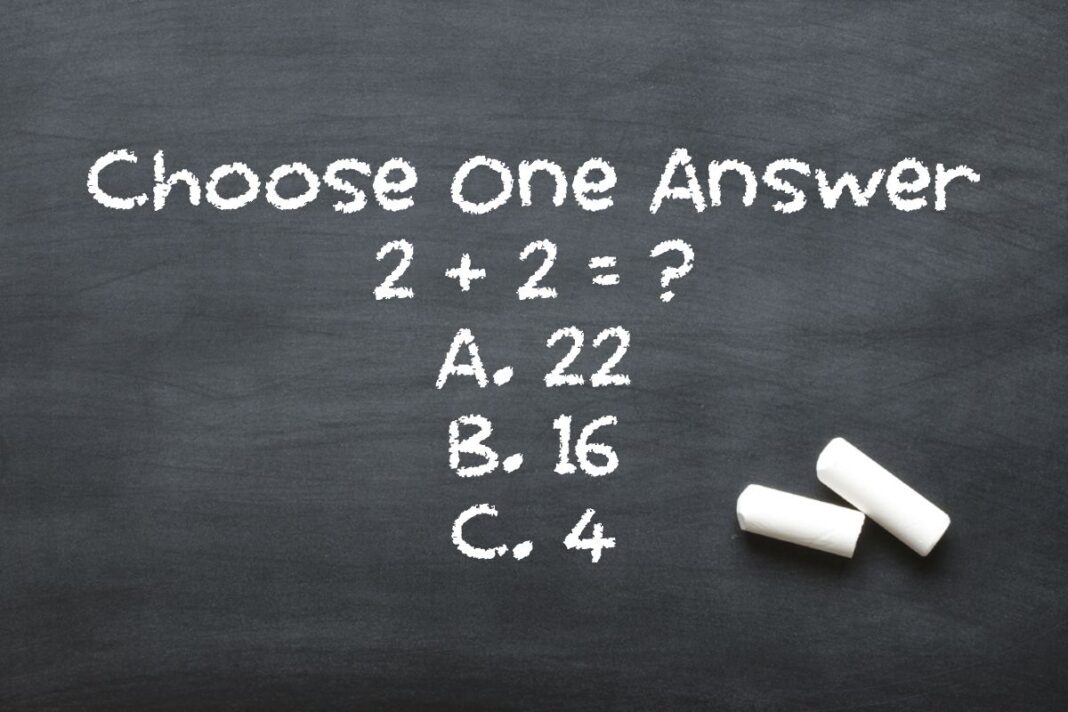

For instance, a certain experimental physics laboratory needs to hire a theoretical physicist who completely understands and can expertly work with all levels of scientific mathematics and theoretical particle physics, and is considering hiring one of three candidates for the one position. What type of test would be best in determining the best candidate for the job? How about a multiple choice test over math and particle physics to determine the most proficient candidate? Would multiple choice answer alternatives (a,b,c, and d) on multiple choice answer sheets eliminate the possibility of chance allowing candidate to answer a question correctly? Let’s examine this issue carefully. In multiple choice examinations, a testee is given a test booklet, an answer sheet, a scratch sheet, a number-2 lead pencil, and a specific test time, usually one-hour. Since the correct answer appears on the examination, depending on the knowledge and skill of the testee, the person has, before beginning the test, a 25 to 30 percent chance of guessing the correct response, either (a, b, c, or d). Let’s say that the dumbest job candidate, a good guesser, actually guesses over-half of the answers and, by luck, succeeds in making the highest score on the test without knowing very much at all about math and science. Is the employer going to hire that person based totally upon that test score? I hardly think so, because responsible private physics laboratories would not determine employee competence based on multiple choice tests, because of their proven unreliability. In most cases, private employers, especially scientific employers, examine their job candidates with pencil and paper tests, where the candidates are required to work-out the complete solutions to math and science problems on blank paper, arriving at the correct answers showing their work and how they determined their answers; since there is only one correct answer to a particular problem.

It was the astute Benjamin Franklin who quipped during the late 18th century that the proving ground of competence in a school classroom should be no different than the practical means of proving competence and proficiency in a job setting; if you know it mentally, you can do it physically. The basic reason for learning to read, write, and perform mathematics is for the purpose of solving practical problems and providing in writing their solutions clearly onto paper for other people to see and understand. In solving math and science problems, one must work each problem out on paper with a pencil and write in proper correct English, using words, sentences, and paragraphs the complete solution. Franklin vehemently intimated that a proficient education allows a person to learn to solve problems and to publish the solutions for the problems. That was why multiple choice testing in American public and private schools was refuted and not regarded as reliable before 1900. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson both stated that the correct answers to math and science problems should never be shown to students who are being tasked with solving such problems. School students should instead be required to ferret-out the correct answers using pencil and paper after being thoroughly instructed by teachers in the math and science curricula.

Unfortunately, however, after 1900, 20th century public school and college educators gradually became inured to multiple choice testing, as did the US military, due to the rise of pragmatism in the declarations of sensational scholars such as John Dewey, Edward Thorndike, Frederick J. Kelly, and Lewis Terman, who collectively promulgated the pragmatic ease with which the testing and grading of mass-numbers of students and recruits could be done, by classroom teachers and educators. Much like John Dewey’s advancement of the (See & Say or Dick & Jane) system of teaching reading in elementary schools instead of teaching phonics, the term (dumbing-down) was first used by noted educator/editor Arthur E. Traxler, who presided as superintendent over the Derby, Kansas School District #6 from 1922-23, in his 1941 book, “Ten Years of Research in Reading: Summary and Bibliography, to describe the deliberate effect of the (See & Say) methodology on the cumulative reading skill of millions of inner-urban public school students over decades of time. Mr. Traxler was very outspoken in his books and articles on the inefficient and unreliable assessment of student performance in the Dewey-molded public education system.

The culmination of standardized testing (SAT, ACT, etc) for college entrance competition in the 1930s, and the incremental inuring of classroom public school teachers to simplistic multiple choice testing has resulted in the awful rise of the inane practice of teaching to tests instead of teaching essential subject curricula (math, science, reading, English, literature, etc.) in public education. The utterly pathetic rise and acceptance of the philosophy of pragmatism after 1900, that the successful end result, whether good or bad, of an educational endeavor justifies any and all means used to achieve that end result, and the egregious demise of objectivity and idealism, has inexorably led to the tragic state of public education in 2025, where over 70 percent of the near-80 million elementary, middle school, and high school students have been improperly assessed in their public school classrooms through the use of improper testing methodology.