“If we lose, I will destroy the world,” said Kim Jong Il, supreme leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Kim’s regime insults all of us. Its very existence is an affront to humanity’s sense of decency and challenges accepted notions of politics, economics, and social theory. More important, North Korea threatens us.

The Great Leader, as Kim now calls himself, can change the course of history with an act of unimaginable devastation. He possesses an arsenal of nuclear weapons and the ballistic missiles to deliver them. Today he can hit most of the continent of Asia and even parts of the American homeland. In a few years–probably by the end of this decade–the diminutive despot will cast his shadow across the globe: He will be able to land a nuke on any point on the planet.

Even now, everyone is at risk. North Korea has said it might sell weapons to others, thereby making itself the first “nuclear Kmart.” Who wants to live in a world where anyone with enough cash and a pickup truck can incinerate a city?

For six decades, America has tried every tactic to stop Kim’s Korea, but it has failed each time. The current approach–providing aid and assurances of security in return for an end to weapons programs–mimics the failed diplomacy of the 1990s. Negotiations, sponsored by China, have yet to produce an enduring solution.

Unfortunately, Kim has paid no price for destabilizing the global order. In fact, many countries, including America, reward him for his fundamental challenge to the international system. Perhaps that is why the world is now further away from a solution to the Korean nuclear crisis than it was a decade ago.

In a contest that will be decided by finesse more than power, Kim is winning. If he ultimately prevails–and time is running out for Washington–his success will probably result in a quick erosion of American power. The world’s strongest nation does not have much of a future if it cannot defend its most vital interests against a reviled autocrat like Kim from a small country like North Korea.

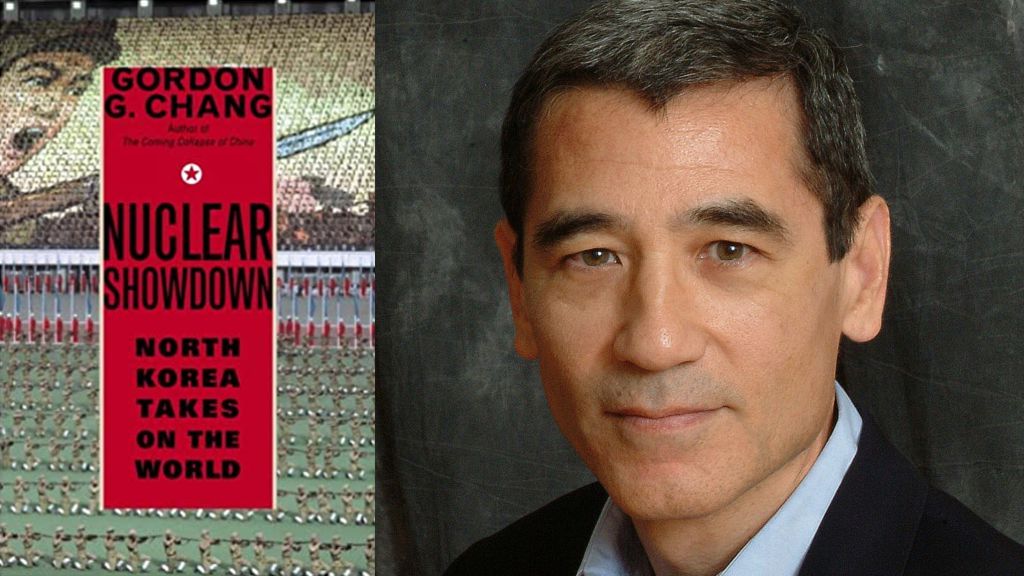

The current conflict with Kim Jong Il is a crisis like no other, perhaps the twenty-first century’s moment of greatest consequence. This is where the world writes its history for the next hundred years. Nuclear Showdown is the first and only major study to look at all dimensions of this crisis. Gordon G. Chang proposes solutions that go beyond the conventional suggestions seen elsewhere.

Nuclear Showdown: North Korea Takes On the World By Gordon Chang was released on January 10, 2006.

Reviews

Advance praise for Nuclear Showdown

“A most thoughtful and challenging book. Chang goes far beyond his immediate subject of North Korea to examine, with unflinching logic, the future of the whole nonproliferation regime, and argues that the stakes in Korea are no less than whether the world is to face a new and many-sided nuclear arms race that we may not survive.”

–Arthur Waldron, Lauder Professor of International Relations, University of Pennsylvania

“Nuclear Showdown is the most readable and complete case for regime change in North Korea there is.”

–Henry D. Sokolski, executive director, the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center

“A page-turner, Nuclear Showdown not only is a superb (and frightening) history of the U.S.—North Korea nuclear confrontation, it also provides important insights into the larger U.S.-China relationship which forms the crucial context for that confrontation–a context Gordon Chang knows so well from his many years in Asia, as well as from his extensive investigation of documents relating to this crisis.”

–Walter LaFeber, Andrew H. and James S. Tisch Distinguished University Professor, Cornell University

About the Author

Gordon G. Chang lived and worked in China and Hong Kong for nearly two decades. He has written for numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Far Eastern Economic Review, and the South China Morning Post, and is frequent lecturer at universities and other institutions in the United States and abroad. He is author of The Coming Collapse of China.

Chapter 1

KU KLUX KOREA

America Creates a Renegade Nation People that are really very weird can get into sensitive positions and have a tremendous impact on history. —Dan Quayle, former American vice president

North Korea insults us. Its very existence is an affront to our sense of decency, perhaps even to the idea of human progress. At a fundamental level it challenges our notions of politics, economics, and social theory. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea—or DPRK as it calls itself—is not only different, but abhorrent.

We abhor something we do not understand. The nation ruled from Pyongyang is seemingly impenetrable; natural and artificial barriers wall it off. Yet the biggest impediment to comprehending North Korea is its very nature: the country defies conventional characterization. We call it communist—but it hardly resembles the other four nations sharing that label. After all, communism, which claims to be the wave of the future, implies modernity. North Korea, on the other hand, is not just backward, it is essentially feudal, even medieval. Many say that the nation is Stalinist, but that’s true only in the broadest sense of the term. Joseph Stalin himself would have been uncomfortable had he ever visited Pyongyang. The regime founded by Kim Il Sung is a cult possessing instruments of a nation-state, a militant clan with embassies and weapons of mass destruction. Kim, unrestrained by normal standards of conduct, created an aberrant society of almost unimaginable cruelty. North Korea is in a category by itself.

It is, from almost any perspective, the worst country in the world. The University of Chicago’s Bruce Cumings, known for nuanced views, calls the nation “repellent,” and American analyst Selig Harrison, always sympathetic toward Pyongyang, admits it’s “Orwellian.” Even leftist Noam Chomsky notes the country is “a pretty crazy place.” How could any nation go so wrong?

The Unfortunate Peninsula

It took centuries of tragedy to produce today’s Koreans, who have endured five major occupations and about nine hundred invasions during their history. Unfortunately for them, the Korean peninsula is where China, Japan, and Russia meet, and so their nation has historically been a prize for powerful neighbors. Yet as painful as its story has been, the last century and a half has been particularly harsh for “the shrimp among whales,” as the people of Korea call their homeland. Perhaps it is no coincidence that this is also the period since the United States became involved in Korean affairs.

America’s first contact with the Hermit Kingdom was a memorable occasion, at least for the hermits. In 1866 the General Sherman, a steam schooner, chugged up the Taedong River toward Pyongyang. After ignoring warnings to turn back from the locals, who were not interested in either American trade or Christian religion, the ship was torched and the crew killed and dismembered.

Despite the unpleasantness in the Taedong River, the Koreans eventually found some use for Americans. In 1882 they signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Washington. This pact, their first with a Western nation, was intended as a defensive measure to ward off Korea’s more immediately threatening neighbors.

The Korean king danced with joy on the arrival of the first American envoy, but that was premature: in a few years Washington would sell out their newfound Korean friends. The Japanese and the Russians were both interested in controlling Korea, and Tokyo proposed dividing the peninsula into spheres of influence along the 38th parallel. The tsar refused. These two powers could not peacefully reconcile their expansionist ambitions. The Japanese humiliated Moscow’s forces in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, the first defeat of a European power by an Asian one in modern history. President Theodore Roosevelt brokered the peace, which confirmed Japanese control over Korea. As part of the deal, Washington secretly obtained Tokyo’s assurance that it would not challenge its control of the Philippines. Roosevelt received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

An American won the award, and Korea paid the price. As a result of Roosevelt’s peace, Japan occupied Korea in 1905 and annexed the place outright five years later. In obliterating the Korean nation, the Japanese brought an end to one of the longest imperial reigns in Asian history, the Choson Dynasty, founded in 1392. Japan’s occupation was especially cruel: the peninsula’s new masters tried to kill off the concept of Korea. They forced their subjects to take Japanese names and tried to expunge the Korean language. Japan imported Shinto, its religion, and taught a new history to schoolchildren. Millions of Korean men and women were impressed into the Japanese war effort, many taken from their homeland. Koreans had to swear loyalty to the emperor in Tokyo.

It took Japan’s defeat in World War II to end the occupation. Although Japanese troops went home, Korea, which technically did not exist during the fighting, was the Second World War’s big loser. The Cairo Declaration of 1943 stated that “in due course, Korea shall become free and independent,” but events—and the Allies themselves—conspired against the Korean people. America, concerned about the casualties resulting from a potential invasion of the Japanese homeland, persuaded the Soviet Union to declare war against Tokyo, which it finally did on August 8, 1945, just seven days before the emperor capitulated. Washington slammed the door on a Soviet occupation of Japan but permitted Moscow a slice of Korea. The Red Army, without firing a shot, invaded the northern part of the Korean peninsula on August 9.

Washington had given no thought in the closing days of the war about what to do with Korea. There were no American troops there, and to avoid a Soviet takeover of the whole peninsula the United States hastily proposed its division. As August 10 became the 11th in the American capital, two junior American Army officers, consulting a National Geographic map, picked the 38th parallel as the border for “temporary” occupation zones. By selecting a line with historical significance, Lieutenant Colonel Dean Rusk, later to become secretary of state, and his colleague inadvertently signaled to Moscow that the United States recognized the tsar’s old claim to the northern portion of Korea. Whatever the Soviets thought, they accepted, and honored, the proposed dividing line. Korea, which had been unified for more than a millennium, was severed.

Korea’s division was an afterthought. There was no justification for the act—if any country deserved dismemberment, it was Japan. In different times, there might have been no consequence to the last-minute decision to split the peninsula into two. In the global competition developing between Moscow and Washington, however, the stopgap measure took on significance. As every business consultant knows, there is nothing as permanent as a temporary solution, and Korea proved this proposition. National elections, to be sponsored by the United Nations, were never held. Eventually each side established its own client state. The American-backed Republic of Korea was officially proclaimed on August 15, 1948, and the Soviet-supported Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was officially born less than a month later.

The new arrangement was in trouble from the beginning. Each of the two states claimed to be the sole representative of the Korean people, and both of them were raring for a fight. Neither big-power sponsor stayed around long to restrain its young ward. Soviet troops were off the Korean peninsula by late 1948, and the Americans decamped by June 1949. Two jealous children were left to settle their fate in zero-sum fashion. Both sides conducted guerrilla raids and battalion-size incursions across the 38th parallel.

On June 25, 1950, Kim Il Sung, the North’s leader, initiated full-scale war by sending his tanks and troops south. President Harry Truman intervened immediately to stop what he perceived to be a Soviet test of Western resolve. The United Nations, prompted by Washington, showed remarkable resolve of its own: for the first time in history a world organization decided, in the words of historian David McCullough, “to use armed force to stop armed force.”

Despite the unified response of the West, Kim’s reunification policy almost succeeded. The North Koreans took Seoul in less than a week and had almost the entire peninsula under their control in a little over a month. Kim’s forces were then beaten back almost to the Chinese border by troops from seventeen countries under the United Nations command led by General Douglas MacArthur. Chinese “volunteers” crossed the Yalu River into North Korea beginning in late October and pushed the American-led coalition south of Seoul by the end of 1950. During the remainder of the war the United Nations forces—primarily Americans—advanced only slightly northward during a period of essentially stalemated conflict.

The fighting during the “Great Fatherland Liberation War,” as the North Koreans call it, lasted for three years and one month. Negotiations went on almost as long: they continued for two years and nineteen days. There were 158 plenary sessions before the parties could agree, and even then they only arrived at an interim arrangement, a cease-fire. To this day there has been no treaty formally ending the conflict, so the war technically continues.

Alt…