Is this new protective coating for fruits and vegetables a cure for food waste or a potential health hazard?

Fruits and vegetables are healthy food choices—but they don’t last. Before you have a chance to eat your avocado, orange, or apple, it may spoil. Within just a few days of purchase, many of these highly perishable foods can turn to trash.

It’s not just a problem in individual households, but a liability throughout the entire supply chain. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), between 30 to 40 percent of the nation’s food supply never makes it to a belly.

One company has developed a product aimed at tackling this problem by substantially increasing the shelf life of foods that tend to spoil quickly.

The company is called Apeel Sciences, and their solution to food waste is called Edipeel: a thin, odorless, tasteless, and colorless film used to coat fruits and vegetables. It’s designed to slow moisture loss and reduce oxidation on produce so it is more likely to make the journey from farm to table.

You probably haven’t noticed this invisible layer, but starting a few years ago, Edipeel has come to cover a variety of produce from all over the world. And its reach continues to grow. Last month, Apeel partnered with a major California-based lemon and avocado grower, Limoneira, to coat their produce. Limoneira also has the rights to license Edipeel to other lemon producers.

In a concerted effort to slow food waste, the grand aim is to make Edipeel an industry standard. Limoneira owner Harold Edwards says his goal is to cover every lemon in the world with Apeel’s coating.

Apeel describes their product as a kind of produce protection which guards against rot and spoilage—mitigating a major weak point that has always accompanied fresh produce shipped from near or far. With claims that Edipeel can increase shelf-life as much as five times as long as produce without this protective coating, it’s easy to see the draw for growers and distributors.

However, some doctors, food advocates, and consumers are not so sure.

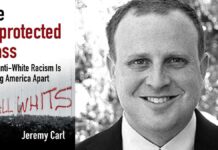

A big part of the suspicion comes from the globalist-minded organizations behind the company. The CEO and founder of the Apeel is a World Economic Forum (WEF) Young Global Leader. And the first grant used to kickstart the company in 2012 came from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

However, concerns about Edipeel are larger than its affiliations. It’s the same concern that comes with any new food additive: Is it healthy, and is it safe?

That depends on who you ask. Regulators around the world vouch for Edipeel’s safety. However, restrictions can vary. The product is allowed for use on all fruits and vegetables in Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Peru, and South Africa, with no restrictions. However, in the European Union, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, Edipeel is permitted only on a handful of produce where the peel isn’t consumed: avocados, citrus, mangoes, papayas, melons, bananas, pineapples, and pomegranates.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration says Edipeel is Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS), and it has even been approved to coat certified organic produce.

What’s It Made Of?

The premise of Edipeel is nothing new. Protective food films have been around for hundreds of years. Distributors have been coating produce with a variety of edible waxes since the 1920s to preserve freshness.

These legacy food films are made primarily from plants. Carnauba wax, for example, comes from a Brazilian palm.

But what exactly is Edipeel? The company website claims that it is plant-based, vegan, non-GMO, and “composed of only food grade ingredients made from materials that exist in the peels, seed and pulp of all the fruits and vegetables we already eat.”

But a definite source for this food film is not so clear. The company gives a lot of details about what it does not contain—particularly common food allergens, such as soy, wheat, and peanuts.

However, the actual raw ingredients for Apeel’s coating may vary. According to a 2016 article in the New York Times, Edipeel is made “Using leaves, stems, banana peels and other fresh plant materials left behind after fruits and vegetables are picked or processed.”

According to the Apeel website, the foundational elements the company uses can be found in virtually any type of plant.

“We put a lot of effort into selecting and adjusting our ingredients based on a balance of sustainability and economics,” states the company.

What’s The Harm?

The source material isn’t what arouses concern as much as what it is turned into. Edipeel critics condemn the chemical alteration of these processed produce leftovers that ultimately end up on your food.

Although it may be derived from fruit and vegetable scraps, Edipeel is a kind of fat. In their GRAS application for the FDA, Apeel explains that their product is manufactured through the “catalyzed esterification of fatty acids with protected glycerol,” as well as the “catalyzed deprotection of the protected fatty esters.”

“These residual solvents and reactants are monitored to ensure the product complies with the appropriate food regulations,” states the document

The final product are emulsifiers known as mono- and di-glycerides which are they also a type of transfat.

Transfats are typically made from an oil (often soy or canola) that is liquid at room temperature but altered to be turned into a solid fat at that temperature. The purpose of the process is to slow rancidity and extend shelf life. Thanks to these attributes, transfats were a major ingredient of processed food for decades. But when a substantial body of evidence revealed that these chemically altered fats raised the risk of heart disease, food manufacturers slowly abandoned them. By 2016, the FDA determined that trans-fats were “unsafe to eat.”

However, the FDA’s distinction only applied to tri-glycerides, not mono- or diglycerides, which are found in Edipeel.

In a short video discussing Edipeel, Dr. Jane Ruby, former pharmaceutical researcher and host of the Dr. Jane Ruby Show, shares a concern that these fats may present increase the risk of heart disease for some people.

“It’s serious because it’s full of mono- and di-glycerides which are going to saturate your blood, and over time make you sick,” Ruby says.

But if these mono- and di-glycerides really are so dangerous, their health concerns extend far beyond Edipeel. Lots of processed foods contain these emulsifiers, either to extend shelf life, prevent separation, or improve a food’s texture. You can find them in baked goods, ice cream, beverages, chewing gum, whipped toppings, and more.

In fact, in a 2017 article from the Journal of Experimental Food Chemistry, about 70 percent of the emulsifiers used in the food industry are mono- or di-glycerides.

But there is no consensus on how safe these emulsifiers are. In its GRAS application, Apeel states that it is “well established and recognized” that monoglycerides (or monoacylglycerides) are “naturally formed in the gastrointestinal tract in the breakdown of triglycerides.”

“Given the metabolic sequel described above, and by applying scientific procedures, it can be concluded that a mixture of monoacylglycerides would not pose any health hazards different from commonly consumed dietary oils derived from plants or animals,” states the application.

However, other research published online in the December 2019 edition of the Wiley Nutrition Bulletin reveals concerns that these “emulsifiers may contribute to gut and metabolic disease development through alterations to the gut microbiota, intestinal mucus layer, increased bacterial translocation and associated inflammatory response.”

But how much of this stuff will we ultimately wind up eating? The GRAS application considers the consumption of a mixture of mono-glycerides as an added food ingredient to be safe at levels up to 218 mg/day (the “maximum daily intake”).

How much Edipeel people will actually end up eating a day is another question altogether.

However much you end up eating ultimately depends on what kind of Edipeel coated produce you consume. For oranges, avocados, and other fruits or vegetables that you peel before eating, the Edipeel coat is discarded. Apeel Sciences says their product is “not expected to migrate through the fruit skin into the edible portions of these foods.”

For things like apples and grapes where you typically do eat the skin, “it is expected that the product will remain on the peel and not present in juice extracted from these or other fruits.”

The primary source of consumer exposure to Edipeel will be raw fruit with edible peels. And unless you like to peel all of your produce before you eat it, you’re likely to eat some Edipeel in the process. Apeel’s website says you may remove a bit of their coating with water and scrubbing, but it’s unlikely that you’d be able to remove all of it without damaging the produce. That’s because you wouldn’t be able to “maintain the fruit’s natural freshness” if the coating was easily removed.

An Illusion of Freshness

Edipeel coated produce is designed to hold up better in the supermarket than plain produce, but does it really maintain its freshness?

In an article discussing Apeel’s product, The Weston A. Price Foundation, a group that regularly warns against innovations that stray from the ways our ancestors ate, says that Edipeel produce only creates the illusion of freshness.

“Informed consumers have long understood that the best way of getting high-nutrient-density fruits and vegetables is to consume in-season produce that is locally grown and organic or biodynamic. This allows them to inspect their produce visually and use appearance as a proxy indicator for gauging freshness and nutrient density. Because Apeel’s barrier coating halts the visual decay of fruits and vegetables (an otherwise natural post-harvest occurrence), it will prevent consumers from knowing how long ago the produce was harvested and, therefore, will make it difficult to make inferences about nutrient density,” states the article.

A case in point was recently posted to Twitter. A consumer who accidentally purchased an Edipeel coated cucumber, decided to do an at home experiment to see how the vegetable will age over time. Over the course of six weeks, the cucumber lost most of its color, but remained firm.

As with any new food innovation, some will embrace it, and some will avoid it. Even if you opt for organics, Apeel has an Edipeel formulation approved for USDA Certified Organic Produce. Since Edipeel is invisible, those who wish to avoid the coating will have to be observant shoppers, and glance at their produce before placing it in their carts. Apeel assures consumers that products which bear its coating will have to say something about it.

“We work with our partner to ensure Apeel produce is labeled so you can make informed decisions,” states the company website.

By Conan Milner